Denis Johnson

Denis Johnson (1949-2017) nació en Munich, pero se crió en Tokio, Manila y Washington. Desde la publicación de sus primeras obras se convirtió en un autor de culto en Estados Unidos. Recibió la beca Lanna Fellowship y el Whiting Writer's Award, entre otros muchos galardones. En 2007 le fue concedido el National Book Award por su novela Árbol de Humo (Literatura Random House, 2008). También es autor de la novela negra Que nadie se mueva (Roja y Negra, 2012) y de las novelas Hijo de Jesús, Sueños de trenes, El nombre del mundo y Los monstruos que ríen, todas ellas publicadas en Literatura Random House.

Denis Johnson is the author of Tree of Smoke, which won the National Book Award for fiction in 2007.Cindy Johnson/

'Train Dreams' Evokes Frontier Life, Fate And Death

ALAN CHEUSE

- Think of the spare straight lines of a Grant Wood engraving. Denis Johnson's striking new short novel about life, fate and death in the early 20th-century American mountain West, leaves that impression — plain yet stark in its depiction of an ordinary man's life both particular and universal. And think of the compactness and pacing of Jim Harrison's masterly novella Legends of the Fall and you'll also gain some idea of what it's like to read Train Dreams. Johnson borrows something of his technique from Harrison, a device I would call emotive exposition, which lends declarative statements of fact a certain kind of dramatic force, and harks back to the work of Hemingway and Sherwood Anderson.

Train Dreamsby Denis JohnsonHere's what Johnson does, as in, for example, the opening paragraphs of Train Dreams:In the summer of 1917 Robert Grainier took part in an attempt on the life of a Chinese laborer caught, or anyway accused of, stealing from the company stores of the Spokane International Railway in the Idaho Panhandle. ... Three of the railroad gang put the thief under restrain and dragged him up the long bank toward the bridge under construction fifty feet above the Moyea River. A rapid singsong streamed from the Chinaman voluminously. He shipped and twisted like a weasel in a sack ...Article continues after sponsor messageThe matter-of-factness of the first couple of sentences about the everyday cruelty of the American frontier partakes of the seeming impartiality and declarative truth of a newspaper account. The shift in the third sentence to the sounds made by the would-be victim eases us, without any difficulty at all, from the realm of the factual to the realm of the dramatic. Johnson works the story of Grainier's un-self-examined life in this same way, from his life laboring on the railroad, clearing forests for track, to his courtship, marriage, his mourning for the wife and child he loses in a huge fire, his eventual work as a hauler and, late in life, in town.Johnson deploys paragraph upon paragraph and scene upon scene in a fashion similar to the way in which, we hear, Grainier himself rebuilds in the Moyea Valley, where before the terrible fire he enjoyed a simple but pleasing domestic life:He built his cabin about eighteen by eighteen, laying out lines, making a foundation of stones in a ditch knee-deep to get down below the frost line, scribing and hewing the logs to keep each one flush against the next, hacking notches, getting his back under the higher ones to lift them into place. In a month he'd raised four walls nearly eight feet in height ...What seems merely descriptive here becomes emotionally evocative. We sense that Grainier is not just rebuilding a structure but attempting to reconstruct his life.In the same fashion, Johnson gives us passages from the natural world, as in the following excerpt in which we see the valley coming back after the devastating fire, that evoke more than just themselves:Animals had returned to what was left of the forest ... clusters of orange butterflies exploded off the blackish purple piles of bear sign and winked and fluttered magically like leaves without trees. More bears than people traveled the muddy road, leaving tracks straight up and down the middle of it. ... Fireweed and jack pine stood up about thigh high. A mustard-tinted fog of pine pollen drifted through the valley when the wind came up ...In this way, Johnson beautifully conveys what he calls "the steadying loneliness" of most of Grainier's life, the ordinary adventures of a simple man whose people are, we hear, "the hard people of the northwestern mountains," and toward the end even convinces us of his character's inquisitive and perhaps even deeper nature than we might first have imagined. Grainier "lived more than eighty years, well into the 1960s," we learn. Most people who read this beautifully made word-engraving on the page will find him living on.Read an excerpt of Train Dreams

Denis Johnson

About Dennis Mill- One of the earliest settlements in this Northwest Georgia area sprang up around a gristmill. Dennis Mill was constructed on Rock Creek in present day Murray County around 1869 and was active for almost a hundred years. The Dennis community was named for Dennis Johnson, who was the mill operator and in later years the postmaster. The community grew to include a post office, a blacksmith shop, a cotton mill, and a sawmill.

- The mill building is two story, roughly 22′ x 60′ in size, and built with pine lumber using timber frame joinery. It has a 22′ x 50′ main floor, a 22′ x 10′ mezzanine, and a 22′ x 50′ upper floor. It currently has a 22' overshot steel wheel at the right end of the building; the original wheel was wood with a steel axel/drive shaft.

- A penstock, turbine and DC generator for electricity were added in the 1940’s.A long narrow ridge line separates the mill from the mill pond. This necessitated a rather lengthy mill race to convey water from the mill pond to the mill. A race was dug into the hillside from the dam along the back side of the ridge, then through a 20′ deep cut through the ridge and then along the front of the ridge to the mill. The race measured 8-10 feet wide and 6-8 feet deep at beginning but reached a depth of more than 20 feet where it cut through the ridge. A 4′ wide x 1′ deep wooden trough carried the water.There is quite a bit of writing on the walls, beams, and doors of the mill. Most appear to be tallys and associated names. One script on the wall near the bin where the meal and flour was bagged says “Do not spit on the floor“. A wall cabinet and one of the grind stone housings has “Cohutta Mills” stenciled on it. Was that an early name for the mill or was some of the equipment moved from another mill?

Two sets of grind stones are located on the mezzanine between the main and upper floors, one for corn and one for wheat. Census records indicate the mill processed 4,264 bushels of wheat along with 408,000 pounds of cornmeal one year. Dennis Mill continued to grind some meal until the early 1950’s.

All of the gearing between the water wheel and the grind stones is intact but currently not operational. The grindstone housings and most of the related equipment is intact. The hoppers over the stones have been stolen. Hoists for lifting the grindstones are intact. A bolter reel hangs from the ceiling.

Dennis Mill, Circa 1869, Condado de Murray

La comunidad de Dennis que creció alrededor de este molino histórico fue uno de los primeros asentamientos en esta sección del noroeste de Georgia. Fue nombrado por Dennis Johnson, quien fue uno de los primeros operadores de molinos y administrador de correos. Una de las piedras de molienda indica que pudo haber sido originalmente conocida como Cohutta Mills, pero esto no está claro. Electrificado en la década de 1940, el molino operó de forma limitada hasta la década de 1950. La estructura original sobrevive y es la pieza central de una propiedad que hoy incluye dos maravillosas cabañas de alquiler a orillas de Rock Creek, conocidas como Dennis Mill Cabins and Events .

Remembering Denis Johnson

When people ask me what Denis was like, I always think about how he listened far more intently than just about any writer I’d ever met.

I first met Denis Johnson in the summer of 2009, through my friend Brian Dille. Brian was a public policy graduate student in Santa Monica, and one of the smartest, most polite people I’ve ever met. I lived half a mile from him in Venice Beach, and I was with a fellow writer, George Ducker, on the patio of a now-defunct bar on Washington Avenue when Brian texted us, inviting us to join him for a few days on Denis Johnson’s property near Bonners Ferry, Idaho.

At this point, I’d just read Tree of Smoke and Jesus’ Son, and this was enough to make me an eternal Denis Johnson fan. I said yes before even hearing the details.

‘It won’t be anything glamorous,’ Brian told us. ‘We’ll be camping outside in tents. We might have to do a lot of work.’

Brian first met Denis in June 2006, at a gala in San Francisco celebrating the Intersection for the Arts’s tenth anniversary. After the performances ended, Brian went up to him right away.

‘I’ve wanted to meet you for a long time,’ he told Denis. ‘Even drove through Bonners Ferry trying to meet you.’ They ended up speaking for nearly thirty minutes, discussing, among other things, Christianity and Sam Shepard.

I only knew Denis as a warm and kind person, but I referenced Brian’s intelligence and politeness earlier because you’d have to know how strong these traits are in him to understand how he could approach Denis as a complete stranger, basically admit to stalking him, and yet somehow end up talking to him for almost half an hour, eventually inspiring Denis to ask, ‘Brian, have you ever done any carpentry?’

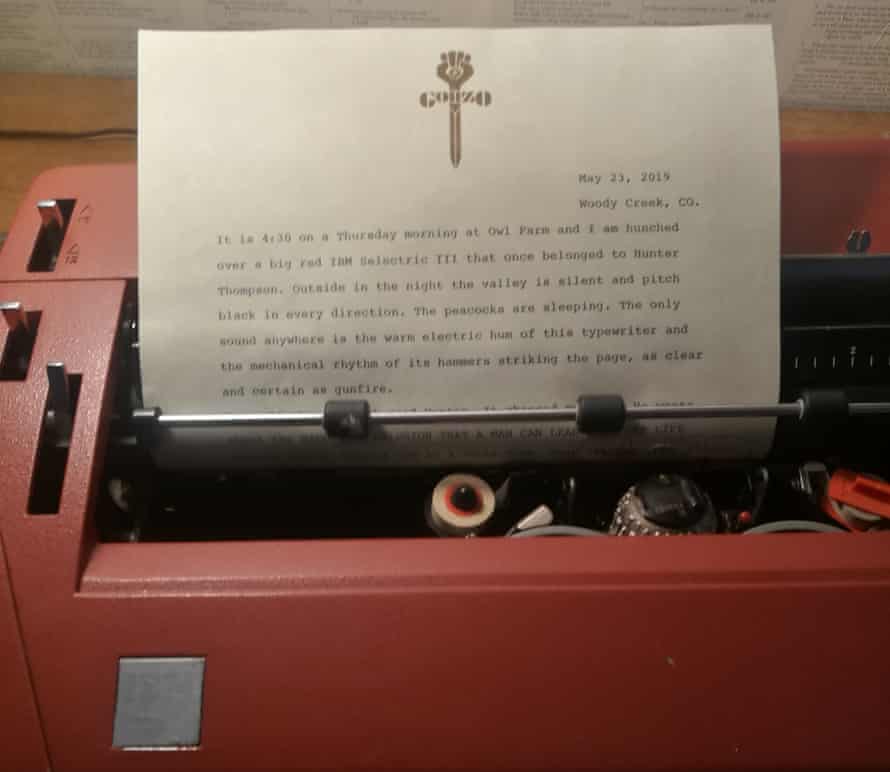

As I understood it, as compensation for work published in McSweeney’s, Eli Horowitz and a dozen or so other men and women, mostly writers, mostly with no carpentry experience, converged on Denis’s land for a week every summer to help him build a guest cabin. It became an annual event which Denis called ‘The Week of Chaos.’ The full story of how this situation came about and its early years is someone else’s to tell, but by 2009 the cabin was nearly finished, and anyone who’d participated in its construction had established equity in someday using it as a writing retreat.

The Writers’ Cabin

Brian forwarded me an old invite to give me a taste:

From: Denis Johnson

Date: Wed, Jun 7, 2006 at 9:15 AM

Subject: Re: cabin building in Boundary County

To: Brian Dille

Dear Brian,

We’d love to have you come — here’s the info I sent out recently —

TO ALL FRIENDS OF CHAOS:

(But especially to you who demonstrated the agility, courage, and navigational skills it took to get to Doce Pasos North in 05)

COME TO CHAOS

Last week in July

Same deal: All who arrive will get shelter from rain and three meals a day and nothing else

MUSICIANS WILL RECEIVE SPECIAL TREATMENT

poets will be treated like slaves

NEWLYWEDS WILL BE FETED (perhaps that means ‘eaten’)

BABIES BORN HERE WILL BE AMERICAN CITIZENS AND HAVE GOOD LUCK ALL THEIR LIVES

ALL WHO ARRIVE WILL BE WELCOME ESPECIALLY BABIES BORN HERE

Same place as last year, same directions

If you fly and you’re too cheap to rent a car from the airport, come anyway. Maybe someone can pick you up.

FORMER VISITORS RAVE:

‘Just like a four-star hotel, only without the four-star rating.’

— Dylana

‘Just like a four-star hotel, only without the hotel.’

— Caitlin

‘I only got two meals a day.’

— Colonel Dog, Hot Air Balloon Forces of North Idaho

‘North Idaho is my Vietnam.’

— Lana

See you last week in July —

DJ

It sounded amazing. The next week, George and I flew to Spokane, where Brian met us in his truck and drove us all into the remote woods of far northern Idaho, to what Brian and many of the other regulars simply called ‘Chaos.’

Denis Johnson’s evolve Jeep

Unlike Brian, I don’t remember many details of my first meeting with Denis. We arrived at his place when it was still light out, and I recall a carved wooden sign by the front door reading ‘doce pasos [twelve steps] north.’ Brian explained that Denis had been sober for a long time, but guests were allowed to bring alcohol, even if the local Mennonites who sometimes came to clean the place up wouldn’t enter the house if there was beer inside. Denis met us outside on the gravel driveway by his yellow Jeep. The Jeep was attached to a trailer that read evolve in black letters on the tailgate. I remember this particular detail only with the help of photographs, but I don’t need help remembering the immediate warmth of Denis and his wife Cindy. As someone born and raised in Minnesota, it soon came to feel something like visiting the home of some long-lost aunt and uncle, who’d bravely combined the gritty utility and off-the-grid mores of my conservative relatives with the inclusiveness and taste of my liberal ones.

We were told the first night that the work on the cabin was basically finished, so Chaos ended up being calm and easygoing. We’d get to spend the time with Denis and his friends just hanging out on their 140-acre property, in exchange for daily chores like cooking, washing the dishes and running errands. A kind Canadian couple who’d been there for a few days was leaving, and so we got to take their spot in a cabin with bunks. A number of people there that year were young relatives of Denis’s and friends of those relatives, and these mostly college-age kids made their own diversions. To them I think Chaos Week was simply an outdoor retreat at the home of a friend’s middle-aged uncle.

Most of the usual crowd who’d initiated Chaos weren’t around that year. A few neighbors, including a man everyone called ‘Barefoot Mike’, joined us for ribs and pizza that first evening. I found out later that he’d authored an influential DIY tome called The $50 & Up Underground House Book. Other visitors from nearby included the local doula and her husband, a retired professor. There was also a couple of pets, the dog Colonel and the cat Hunter S. Thompson. Over twenty of us ate together outside on picnic tables every day as Colonel wandered among us.

Denis was divinely relaxed, sensitive and uncommonly open. A few hours after George and I met him, he started to weep as he told us the story of a theater director friend of his who’d passed away. He listened with great interest at our stories and tolerated our ignorance and awkward gratitude. That first year I never once spoke to Denis about his books other than to very briefly thank him for them. The only conversation I had in my time there about Denis’s work was with Cindy, when she told us her story of how she agitated against the New Yorker’s editorial choice to cut the last line of ‘Car Crash While Hitchhiking’. The piece ended up being published in the Paris Review, last line intact:

‘How did the room get so white?’ I asked.

A beautiful nurse was touching my skin. ‘These are vitamins,’ she said, and drove the needle in.

It was raining. Gigantic ferns leaned over us. The forest drifted down a hill. I could hear a creek rushing down among rocks. And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.

Cindy was as open as Denis and also intensely interested in us, which made us comfortable. She’s an incredibly brilliant and kind person. Some of my favorite memories of the time I spent in Idaho are doing the dishes with her after dinner.

I took only one photo of Denis (from behind, while he was driving his Jeep) and never once asked him to sign a book or discuss writing, either his or mine. Maybe other people did. I just felt that there’s a time and a place for that kind of thing and this wasn’t it. The splendor of his ease leveled many of our incipient imbalances. This man’s on vacation and thusly, so are we.

I suppose as a professional observer, Denis had some sense of how those of us aspiring writers around him were observing him and taking mental or literal note of things he said. I was self-conscious about being conspicuous about it. I had never spent much time around any celebrated author before and those I had briefly met were often guarded and aloof. To me, Denis wasn’t just the usual ‘famous author,’ this was a writer whose stories made me cry, whose books bonded me with friends and relatives. As someone who never attended an MFA program and had just a few personal writing mentors, I craved the opportunity to get to know a brilliant writer whose work I’d loved and admired for years. As far as I was concerned, though, I had no authority to meet this guy – I hadn’t earned my spot at the table. In the summer of 2009, I had exactly one published short story to my name and a few hundred rejections. I had a lot to learn, and much more work to do. Still do, on both counts.

While I didn’t meet Denis as a student, and I rarely felt like one around him, he could still never be someone I wouldn’t try to learn from. I hope it didn’t bore or annoy him, because he just about seemed to have it all figured out. Looking back, Denis could’ve never left his office the entire time and I wouldn’t have thought less of him, and maybe some cowardly piece of my heart would’ve preferred that. Instead, The Week of Chaos became something more uncomfortable and wonderful: an exercise in learning how to hang out with an idol.

*

One morning, George, Brian and I were able to get a peek inside Denis’ office, which was in its own small outbuilding overlooking a pond. He was one of those writers who faced a window, and the nearest wall was clustered with clippings and notes. He had handwritten a quote of Emerson’s at just about eye-level that read, ‘God will not let his work be made manifest by cowards – Self-Reliance.’

I was awed, but I felt like an intruder. I decided after then to not learn anything he didn’t invite me to learn, and to keep myself open to whatever might be out there in Idaho.

At some point it came out that Denis owned an AK-47. He said it had been a while since he’d fired it and would we like a try. I grew up in a Midwest family that’s extravagant about gun ownership, but at that point, I hadn’t fired a gun since high school.

AK-47s have the reputation of being remarkably hardy and facile but I had trouble chambering my first round.

‘Come on, you wimp!’ Denis said.

Is it weird that I was kind of delighted when he said that? He was right, after all. Any man in my own family would’ve said the same.

I figured it out, and emptied most of my clip into a rotting log. It made me think of the John Prine song ‘Paradise.’ Empty pop bottles was all we would kill.

J. Ryan Stradal firing Denis Johnson’s AK-47

After dinner one evening we gathered in Denis and Cindy’s living room and watched a VHS tape of a Steppenwolf Theater production of True West, starring John Malkovich and Gary Sinise. I had never seen True West before and this experience was made all the more staggering by the knowledge that Denis had repeatedly watched this particular version of this particular play.

Before that trip, I was unfamiliar with Denis’s love for the theatre and his own work in that realm. Denis told George some time later that the theatre taught him to respect everyone and mellow out. He described the actors as being so selflessly ready to work, that he decided that was really how he should be aspiring to be. ‘Before, it was just get out of my way, or find another Denis Johnson. Now I just want to be an employee.’

Denis did not strike me as a man who had any time for irony or the idea of guilty pleasures. He loved what he loved with ferocity, and witnessing his deep emotion and enthusiasm for this decades-old theatre production was as close as I ever came to understanding what his writing students may have experienced, how someone’s informed love dilates love and its possibilities for a listener.

In act two of True West, Lee’s manic search for a pencil incited an intense reaction in Denis; pay attention, he was saying to us, you’ve never seen anything like this. It made me think of that famous moments from Jesus’ Son when the narrator describes a woman’s reaction to her husband’s death: ‘What a pair of lungs! She shrieked as I imagined an eagle would shriek. It felt wonderful to be alive to hear it! I’ve gone looking for that feeling everywhere.’ The feeling I was looking for in life was in Denis at that moment. Anyone who witnessed his fervent, unguarded emotion would search the world for it.

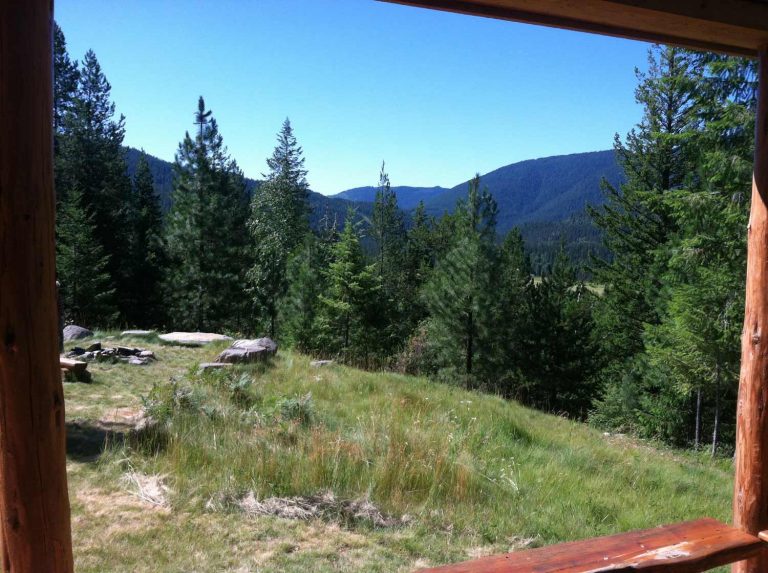

A view from the deck at Chaos

We spent one day driving into rural Montana in Denis’s yellow Jeep – Brian, George, myself, a nice dude from Cornell named Jim, and Denis at the wheel. He was an expert at off-roading in a vehicle he said was a ‘pavement princess’ when he purchased it. He led us to a wild huckleberry patch and drove us through the woods for hours until we eventually found a road and wandered toward the town of Moyie Springs. We stopped at a combination gas station and bar that made Denis apprehensive. ‘They don’t like me in here,’ he told us, but we all went in anyway. A sign by the door promised to 86 anyone caught fighting inside.

George, Brian and I drank bottles of Budweiser. I think Denis ordered a Diet Coke. The bar was dark, even in the afternoon, but it was empty, and whatever menace Denis hinted at never revealed itself. Still, I love what his comment buried under an otherwise idle thirty minutes. I felt like he unspooled narratives all around us, consciously or not, and the conjectures he invited through an offhand comment entering a roadside bar or while examining the tracks around a huckleberry bush were intoxicating. I was already maturing into the kind of writer who was inspired by questions, not ideas, and witnessing the vigor in which he apprehended the world was both recalibrating and rejuvenating. It feels good to wonder, to be puzzled, to sit in dark bars waiting for something to happen, eyes and ears unnaturally alert. Even when you’re not exactly right, it feels good to have guessed.

I spent more time than I should’ve at Denis’s place idly reading. I finished the Brian Evenson and Aimee Bender books I’d brought, and read Stories, by Scott McClanahan, an author I’d spotted on Denis’s shelf whom I’d never heard of before. From where I sit today, it’s tempting to view these relaxing, edifying hours as a waste of time. I’m sure that Denis didn’t want me or anyone else hanging on his elbow every minute, but as Eli put it when we exchanged emails after Denis died, ‘Even as it was happening, I just wanted to remember every single thing he said,’ and I regret not putting myself in more situations where I could’ve just listened to him. That said, there was also a discretion surrounding our interactions that I wanted to keep secure, and I wanted to honor his privacy. I never would’ve written any public account of Chaos for any reason while he was alive. Maybe other people have. Still, there’s some things we talked about that I do remember and won’t discuss here or anywhere.

One of the women at Chaos, Ariel, who was a friend of Denis’s niece Dylana, brought a boom box outside to the wooden porch facing the pond. Someone had a mix CD with the song ‘Mistadobalina’ by Del tha Funky Homosapien. We repeated that one song so many times, it wandered into everyone’s brains, and even Denis started idly singing it while doing chores. Sure, I can’t remember 90 per cent of what he said during his lengthy, soulful conversations with us. But I can remember watching him coil a hose, mumbling ‘Mr Dobalina, Mr Bob Dobalina,’ and it was beautiful.

The next time I made it up for Chaos was three years later. The cabin was long-finished by now, and this would turn out to be the final Chaos ever. Denis had just returned from Central Africa, where he’d been researching The Laughing Monsters. He told us that he’d written another book so he’d have the money to buy his neighbor’s property.

He’d returned from Africa weary and ill. This time, there would be no Jeep trips into the woods, no AK-47 rounds unloaded on fallen trees, not that we minded. In the afternoons we did short hikes, lounged on Denis’s deck, played board games, ate fruit, tried to play soccer on an uneven, sloping lawn, listened to Denis’s experiences in Africa, and talked about books and religion and travel. For the first time, someone took a picture of Denis and I together. It’s not posed, it’s out of focus, and he’s exuberant, smiling at someone out of the frame. To me, that’s who he is. In the middle of nowhere but surrounded by friends, generously engaged, overjoyed just to be here.

When people ask me what he was like, I always think about how he listened far more intently than just about any writer I’d ever met, and held so much emotion in his eyes and his throat when he spoke of people and things he loved. He was always far more patient and kind than he ever had to be to a bum from California, and his unique combination of candor and sensitivity is something I never expect to see again unless I’m uncommonly fortunate. We’ll never come close to reproducing him or his writing, but we’d all do well to imitate his kind, resolute engagement with the world, and maybe we’ll get a little closer.

- http://evanhix.com/dennismill/https://granta.com/remembering-denis-johnson/

- https://www.megustaleer.com/autor/denis-johnson/0000025910

- https://www.npr.org/2011/08/25/139874940/train-dreams-evokes-frontier-life-fate-and-death?t=1613251674776