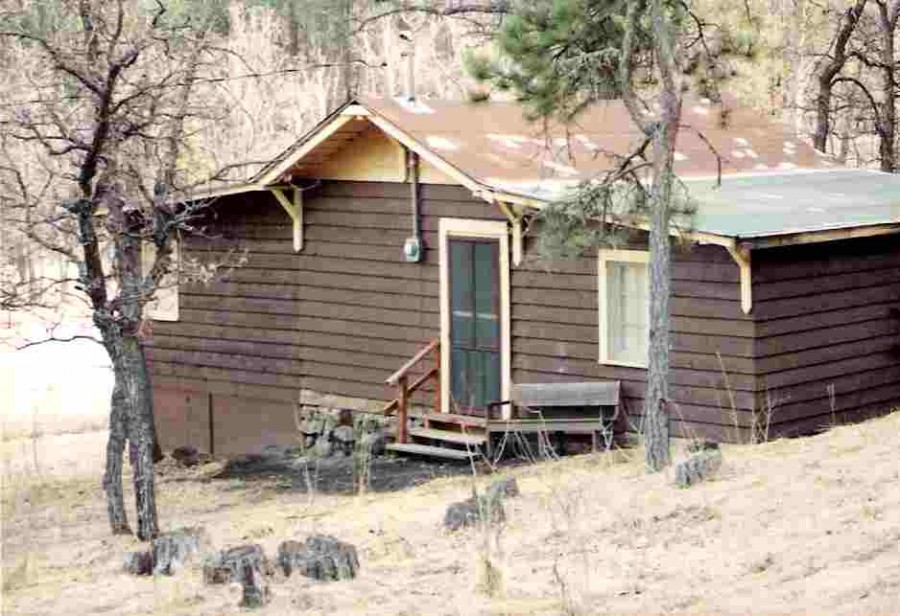

Known as the “Poet of the Sierras," Joaquin Miller was perhaps best known for his poem “Columbus.” His cabin stood along 16th Street for 30 years until threatened with demolition as the new park was being planned. He is quoted as saying, "I sit up here in my fine cabin, while the President himself sits down there at the end of the street with his little cabinet."

Miller’s creative writing began with his assumed name; his real name was Cincinnatus Heiner (or Hiner) Miller. He was born on September 8, 1837, a date that frequently changed during his lifetime. The name "Joaquin" was adapted later from the legendary California bandit, Joaquin Murietta.

Born to Quakers in Indiana, the family moved to Oregon and settled on a small farm. His often cited exploits included a variety of occupations, from mining camp cook, lawyer, judge, newspaper owner and writer, Pony Express rider, and horse thief. As a young man, he moved to northern California during the Gold Rush, and apparently had a variety of adventures, including a year living in a Native American village and being wounded in a battle with Native Americans. A number of his works, Life Among the Modocs, An Elk Hunt, and The Battle of Castle Crags, draw on these alleged experiences.

About 1857, Miller supposedly married an Indian woman named Paquita and lived in the McCloud River area of northern California; the couple had two children. Miller then married Theresa Dyer (alias Minnie Myrtle) in 1862, and had three children with her. The couple divorced in 1869. Miller married for the third time in 1879 to Abigail Leland in New York City.

He was jailed briefly in New York for stealing a horse, and various accounts give other incidents of his repeating this crime in California and Oregon. Despite that fact, Miller found his way to Canyon City, Oregon by 1864 where he was elected the third Judge of Grant County; his log cabin built there is still standing as well.

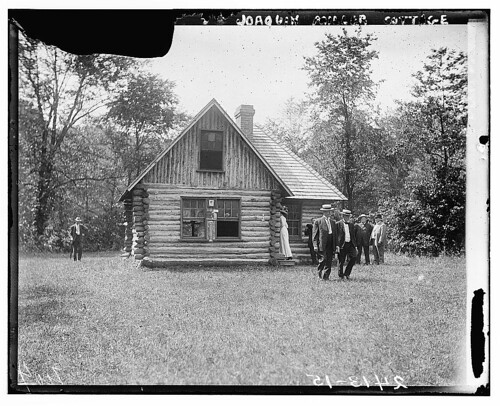

After losing his bid for a seat on the Oregon Supreme Court, he left the Pacific Northwest and spent some years traveling, living in and visiting England, New York, San Francisco, Brazil, and Washington, DC, where he built his cabin on Meridian Hill in 1883. Disappointed at not being appointed as Ambassador to Japan, about 10 years later Miller settled in the Oakland Hills of California. He gave his Washington cabin to a friend, who soon gave it to the Sierra Club. In 1912, one year before Miller's death, the National Park Service became its reluctant new owner.

The California State Association had sought to move it to Rock Creek Park, but the Park Service had refused the request. It was only after Senator John D. Works of California intervened successfully that the cabin was disassembled, moved, and rebuilt at its current location.

From 1893 to his death 1913, Miller resided on a hill in Oakland, California, in a home he called "The Hights"[sic]. He planted hundreds of trees and even built his own funeral pyre on the property. The Hights was purchased by the city of Oakland in 1919 and eventually became the Joaquin Miller Park, a designated California Historical Landmark.

Fellow author Ambrose Bierce once called Miller "the greatest-hearted man I ever knew" but was also quoted as saying that he was "the greatest liar this country ever produced. He cannot, or will not, tell the truth."

Miller's poem “Columbus” was once one of the most widely known American poems, memorized and recited by most school children of the era. It reads:

"Behind him lay the gray Azores,

"Behind the Gates of Hercules;

"Before him not the ghost of shores,

"Before him only shoreless seas.

"The good mate said: 'Now must we pray,

"For lo! the very stars are gone.'

"Brave Admiral, speak, what shall I say?

“Why, say, ‘Sail on! sail on! and on!’”

His other poems include “Songs of the Sierras,” “Songs of the Sun-Lands,” and “The Ship in the Desert.” In 1909, six volumes of his collected poems and other writings were published. He died in Oakland on February 17, 1913. (...)