Ludwig Wittgenstein’s exile in Skjolden, Norway as a cultural self-technique:’To work on oneself’ one needs to be in the right place

„Die Denkbewegung in meinem Philosophieren müßte sich in der Geschichte meines Geistes, seiner Moralbegriffe & dem Verständnis meiner Lage wiederfinden lassen.“ (Wittgenstein, november 1931)“We live in the description of a place and not in the place itself.” (Wallace Stevens)

“The true matter of his thinking, going as it does to the very heart of our culture, is difficult to grasp, yielding only to an effort of thinking that matches the original in courage and power.“ (James C. Edwards, Ethics without Philosophy: Wittgenstein and the Moral Life, 1982)“Geography is simply a visible form of theology.” (Jon Levenson)“A desert-mountain environment (or any landscape, for that matter) plays a central role in constructing human subjectivity, including the way one envisions the holy. The place where we live tells us who we are — how we relate to other people, to the larger world around us, even to God. Meaningful participation in any environment requires our learning certain “gestures of approach” or disciplines of interpretation that make entry possible. All these are matters essential to the analysis of any spirituality.(-)This intimate connection between spirit and place is hard to grasp for those of us living in a post-Enlightenment technological society. Landscape and spirituality are not, for us, inevitably interwoven.” (Belden C. Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, p.9)“No technique, no professional skill can be acquired without exercise; nor can the art of living, the tekhê tou biou, be learned without askesis that should be understood as a training of the self by oneself.” (Foucault)

” Once we see Wittgenstein as an exile, I think this enables us to better understand some things about his life and thought. (-) I think it also helps us to better understand his conception of the philosopher and the role of philosophy.”

For a long time most biographers and Wittgenstein reseachers barely mentioned Wittgensteins relation to distant Skjolden.

In the book ‘Wittgenstein and Norway‘ (1994) it is regarded as little more than ‘a whim’. It was seen as having no greater significance for understanding his philosophical work outside being a calm and undisturbed place where the philosopher could consentrate on his work. In Cambridge Wittgenstein on the other hand seldom could work as he wanted, he complained that was unable to think ceatively in this environment and even that he hated it.

In the book ‘Wittgenstein and Norway‘ (1994) it is regarded as little more than ‘a whim’. It was seen as having no greater significance for understanding his philosophical work outside being a calm and undisturbed place where the philosopher could consentrate on his work. In Cambridge Wittgenstein on the other hand seldom could work as he wanted, he complained that was unable to think ceatively in this environment and even that he hated it.

Richard Wall argues in his book ’Wittgenstein in Ireland‘ (2000) that the philosopher needed to be in thinly populated, exposed and almost barren landscapes that corresponded to his asceticism or his ascetic attitude to life.

In 1948,Wittgenstein wrote in a letter from Kilpatrick house in Ireland:

“I am well. The winter has been very mild so far, even if fairly wet. I would not find the district here very attractive, if the colors were not often so beautiful. I think it must be because of the atmosphere, because not only the grass, but also everything brown, the sky and the sea, are lovely. I feel much better here than in Cambridge.”

“….why the philosopher (-) would build a hut in Norway – of all places…” (Ivar Oxaal, 2010)

“the landscapes in which Wittgenstein spent time while he was working, had an influence on his thinking.”

This article is still under development and represents a comprehensive attempt to take a closer look at all the different well elaborated ways to understand Wittgensteins relation to Skjolden.

Why the norwegian exile?

‘But where shall wisdom be found? And where is the place of understanding?’ (Job 28:12)

From his norwegian exile Wittgenstein is writing both philosophical works, but also the famous notebook the ‘Skjolden Diary‘ (later published as ‘Denkbewegungen‘ in german and ‘Culture and value‘ in english) from the last part of 1936 and first half of 1937. Wittgenstein composed parts of his two most important philosophical and personal texts while visiting Skjolden and staying in his mountain cabin. Both the solitude and calmness and the landscape in itself was in a fundamental way necessary for his regaining an ability to do philosophical work. In a letter to Russel during his second stay in Skjolden in nov. 1913 he writes:

From his norwegian exile Wittgenstein is writing both philosophical works, but also the famous notebook the ‘Skjolden Diary‘ (later published as ‘Denkbewegungen‘ in german and ‘Culture and value‘ in english) from the last part of 1936 and first half of 1937. Wittgenstein composed parts of his two most important philosophical and personal texts while visiting Skjolden and staying in his mountain cabin. Both the solitude and calmness and the landscape in itself was in a fundamental way necessary for his regaining an ability to do philosophical work. In a letter to Russel during his second stay in Skjolden in nov. 1913 he writes:“being alone here does me no end of good, and I do not I could now bear life among people. Inside me, everything is in a state of ferment.”

” – work on philosophy- like work in architecture in many respects- is really more work on oneself. On one’s own conception. On how one sees things. (And what one expects of them”) (CV)

“My own impression is that at some moment in his life – perhaps a moment of great difficulty and even despair – Wittgenstein may have made a resolution to live the rest of his life in a certain way and with a certain aim, and not to let himself be deflected by anything from this resolution. The aim might be described as that of doing his utmost to help others to think correctly about the important problems of life. To do this required that he should devote every bit of his time and energies with complete seriousness to the task and not allow himself to be distracted by lesser considerations of any nature.” (McGuinness, 2002, p. 6)

Today it is becoming clear to us that it is almost impossible to understand the full meaning of Wittgenstein’s philosophy without understanding the background for his writing those diary notes from an exile in a dark and isolated mountain cabin. Some years before, he gave the following remark about his Norwegian exile:

… it seems to me that I had given birth to new movements of thought within me. (1931, MS 154)

Some words on Wittgenstein’s locational biography

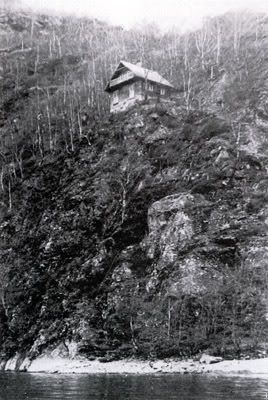

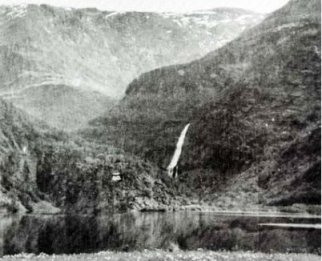

Some words on Wittgenstein’s locational biographyThe austrian thinker Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in Vienna in 1889. He emerged on the international philosophical scene early in last century, between 1910 and 1920. Almost the same time as he developed his original path of thinking he began his lifelong relationship to the distant village of Skjolden in the western fjordland of Norway. From then on, Wittgenstein would be visiting and in periods also living in what is the deepest part of 200 kms. long Sognefjord. The period between 1913 and 1951 he was in shorter or longer periods working out his philosophy in isolation from his familiar surroundings and circle of people. He even moved out of the village, and build himself a secluded place in the mountainside where he lived by himself in a relatively small and completely secluded cabin. The cabin measured 7x8m: this tiny place was called ‘little Austria” by the locals.

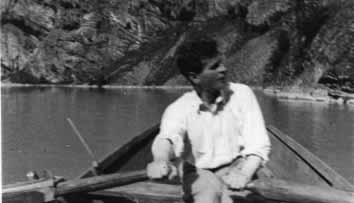

In 1913, he came together with his friend David Pinsent to Skjolden. The following the year he designed and got his cabin built in the mountainside by the Eidsvatn.

His friend Moore writes:

“At the beginning of 1914 he came to see me in a state of great agitation and said: “I am leaving Cambridge….”“Why” I asked. “Because my brother-in-law has come to live in London, and I can’t bear to be so near him.” So he spent the rest of the winter in the far north of Norway”.

“he returned to Norway alone and took up residence on a farm at Skjolden in Sogn north-east of Bergen. Here he lived for most of the time until the outbreak of the war in 1914. He liked the people and the country very much. Eventually he learned to speak Norwegian fairly well. In an isolated place near Skjolden he built himself a hut, where he could live in complete seclusion.”

When Wittgenstein in 1914 told his philosophical friend Bertrand Russell that he wanted to go far away, to Norway – Russel reacted instinctively:

When Wittgenstein in 1914 told his philosophical friend Bertrand Russell that he wanted to go far away, to Norway – Russel reacted instinctively:“I said it would be dark, and he said he hated daylight. I said it would be lonely, and he said he prostituted his mind talking to intelligent people. I said he was mad, and he said God preserve him from sanity. (God certainly will.)”

“(he was) … in a heightened state of intellectual intensity, which verged on the pathological.”

“It is as though I had before me nothing more than a long stretch of living death, (-) I cannot imagine any future for me other than a ghastly one. Friendless and joyless.“

“Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.”

“Death is not an event in life; we do not experience death.”

The dark ages are coming again: Wittgenstein’s monasticism or his monastic approach to life and philosophy

The dark ages are coming again: Wittgenstein’s monasticism or his monastic approach to life and philosophy“Was there a single model exemplified in his life and thought or were there conflicting elements in his views as in his personality?” (Brian McGuinness, 2002, s.17)

It took Wittgenstein days and weeks and maybe months to finally decide where to stay when he was working and writing on philosophical matters. Is it pure coincidence that he in the end should decided that the best place for him to work for so many of his years was the distant little village of Skjolden in the deep end of the Sognefjord?

It took Wittgenstein days and weeks and maybe months to finally decide where to stay when he was working and writing on philosophical matters. Is it pure coincidence that he in the end should decided that the best place for him to work for so many of his years was the distant little village of Skjolden in the deep end of the Sognefjord?To human beings, with a vast inner memory and imagination, places can never be neutral and objective. We create the places we think we are finding or discovering. The Danish author Karen Blixen wrote these words about finding her place, for her it was Africa:

“Here at long last one was in a position not to give a damn for all conventions, here was a new kind of freedom which until then one had only found in dreams!”

They seem part of the approach to Wittgenstein’s life and work that an artist has illustrated in a picture called‘Wittgenstein light’. Efforts to understand the longterm development of Wittgenstein’s life situation in relation to his philosophy and thinking often seem ’light’.

They seem part of the approach to Wittgenstein’s life and work that an artist has illustrated in a picture called‘Wittgenstein light’. Efforts to understand the longterm development of Wittgenstein’s life situation in relation to his philosophy and thinking often seem ’light’. The Tolstoy theory and the simple life

The Tolstoy theory and the simple life“It was as a volunteer officer in the Great War that Wittgenstein happened upon a copy of Tolstoy’s Confession. As Kjell Johannessen of Bergen’s Wittgenstein Archives sees it, the philosopher’s whole Norwegian adventure can be interpreted in Tolstoyan terms as a flight first from Vienna, and later from Cambridge, a university he unflatteringly described as a mutual admiration society. The people of Skjolden were Wittgenstein’s Russian peasants, who left him to live in his own silence.” (Lesley Chamberlain)

“Ludwig was very cheerful this morning, but suddenly announced a scheme of the most alarming nature. To wit: that he should exile himself and live for some yearsright away from everybody he knows –say in Norway.That he should live entirely by himself- a hemits life – and do nothing but work in logic.”

“the dark ages are coming again….(-) I wouldn’t be surprised if you and I were to live to see such horrors as people being burnt alive as witches.”

Human life and the living human mind is embedded in a complicated structure of contexts; some of them directly experiential, others not – not only the close immediate and visible situation. Often, the mind is recursively constructing and making up imaginary contexts for itself to relate to and live in. So, there is also a broader context for Wittgenstein’s scenery message; the context of the philosopher’s life in Austria and England and Europe between the wars; a context that gives even more meaning to these few words about himself and a wonderful scenery.

Wittgenstein was all his life extremely conscious about the distance between himself and the time he was living in:

‘My type of thinking is not wanted in this present age; I have to swim so strongly against the tide.’

“….I have no sympathy for the current of European civilization and do not understand its goals, if it has any. So I am really writing for friends who are scattered throughout the corners of the globe.” (CV, 6)

“since his death Wittgenstein seems to have become the victim of everything he hated most.”

In the book ‘On the trail to Wittgenstein’s hut(2010) the norwegian author Ivar Oxaal has a different and more positive view of some of the reasons behind Wittgenstein’s decision about going to Norway. Oxaal tells that Wittgenstein’s interest in going to Norway arose during the period following Scott’s and Amundsen’s explorations. It was hen further stimulated by the Titanic disaster in 1912.

Wittgenstein as exile-theory

Klagge (2011) has formulated the exile theory about Wittgenstein; he writes about this idea -

Klagge (2011) has formulated the exile theory about Wittgenstein; he writes about this idea -“But his sense of exile is as much temporal as it is geographical: Wittgenstein thought of himself as at home in an earlier era.” (p.2)

Klagge point out that “exile” is a term that Wittgenstein also used to describe himself. On his first visit to Norway in 1913 his companion David Pinsent writes about Wittgensteins philosopical plans that -

“he swears he can never do his best except in exile.”

“This kind, friendly letter [from Pinsent] opens my eyes to the fact that I am living in exile [Verbannung] here. It may be a healing exile, but I now feel it as an exile all the same.” (Geheime Tagebücher: 1914-1916, ed. W. Baum, Vienna: Turia & Kant, 1991).

The inner and the outer landscape

In a notebook from 1938 Wwittgenstein wrote:

‘Whoever is unwilling to descend into himself, because it is too painful, will of course remain superficial in his writing.’

‘The truth can be spoken only by one who rests in it; not by one who still rests in falsehood, and who reaches out from falsehood to truth just once.’

This calm and gray autumn day in 1936, from his exile in the mountain slope, Wittgenstein is looking into the greenish lake through the window in the front of his small hut. So, he has once more chosen to distance himself from the people he knows, to live all alone for some months. In his exilic existence he will be struggling with thoughts about language and logic, and often even more about the times he is living in, himself and his own soul. Solitary and colorless days are passing in the steep hillside among the mountains. To catch how Wittgenstein is experiencing his exilic life, one is tempted to borrow some telling words written by the american author Cormac McCarthy: “the days more gray each one than what had gone before“. Wittgenstein is thinking, writing, working and struggling – as he saw it himself he is in different ways struggling against dangers and temptations of the dominant culture and society of his times.

This calm and gray autumn day in 1936, from his exile in the mountain slope, Wittgenstein is looking into the greenish lake through the window in the front of his small hut. So, he has once more chosen to distance himself from the people he knows, to live all alone for some months. In his exilic existence he will be struggling with thoughts about language and logic, and often even more about the times he is living in, himself and his own soul. Solitary and colorless days are passing in the steep hillside among the mountains. To catch how Wittgenstein is experiencing his exilic life, one is tempted to borrow some telling words written by the american author Cormac McCarthy: “the days more gray each one than what had gone before“. Wittgenstein is thinking, writing, working and struggling – as he saw it himself he is in different ways struggling against dangers and temptations of the dominant culture and society of his times.As he is writing the words about the serious landscape Wittgenstein has started writing down what later will be known as “Philosophical investigations“, his most important late work published two years after his death in 1951. As we are observing him and his personal and solitary struggle we have to ask: What is going on a deeper level; can we know why Wittgenstein is choosing for himself such a form of life?

The facts are there for all of us to read about and even to see: Wittgenstein is living for weeks and months most of the time completely alone in the middle of a landscape of towering mountains, turbulent waterfalls, a little lake almost green from glacier waters, further away behind the small white houses in the village he can see the vast Sognefjord. It is a landscape that feels quiet and serious, it owns a calm and quiet seriousness. And first, the deep silence he feels as he is working days and weeks in his solitary cabin and looking out into the scenery.

As we go back to read and try to decode the message in these famous words about the Skjolden landscape written by Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1936, we often unknowingly do the same mistake all of us. It is not easy to avoid it, ‘non-Wittgesteinian’ as we all instinctively are. I am pretty sure that you, the reader of this article, automatically did this small mistake.

What is it ? We are immediately thinking about the outer landscape that Wittgenstein seems to describe, how it looks or feels like. If we stop and think it over for a moment, we can understand that Wittgenstein is not only talking about the landscape and the surroundings in this faraway place by a fjord in Western Norway. He is actually as much and maybe more expressing himself and sharing this thoughts with us about his inner landscape, he is communicating and talking about himself, how he feels about his relations to these surroundings. He is recreating the world in his own picture and showing us this picture.

As a philosopher Wittgenstein always understood that thinking basically is rooted in personal life; as he says -

“‘Wisdom is grey’. However life and religion are full of colour”.

“Some philosophers(or whatever you like to call them), suffer from what may be called ‘loss of problems’. Then everything seems quite simple to them, no deep problems seem to exist any more, the world becomes broad and flat and loses all depth, and what they write becomes immeasurably shallow and trivial”.

How can we live our lives like that? What is the best way to do that? To answer this question, I think one need more than a short article of space. As we all know, there are different ways; modern ways and older traditional ways.

Wittgenstein wrote of himself to a friend; “I am not a religious man“, but still we know that he at the same time he had strong sympathy for and some sort of attraction to religious thinking. How can that be?

In the first centuries after the crucifixion of Christ, the desert fathers went to live for up to 40-50 years in isolation in the harsh desert, hidden from other people in deep solitude and deeper caves; all the time to ‘work on themselves‘. What William Harness writes in his book ‘The desert christians. An introduction to the literature of early monasticism‘ (2004) could also with good reason be written about Wittgenstein:

“It’s that way for someone who lives among human beings. The agitations, the shake-ups, block one from seeing one’s faults: but once one becomes quiet, still, especially in the desert, then one sees one’s failings.”

“Die Einsamkeitsorte zeichnen sich gewöhnlich nicht nur durch die Abwesenheit von Menschen aus, sondern auch durch ihre Einförmigkeit und Homogenität: Wüsten, Meere, Wälder, Steppen oder Schneefelder bilden (zumindest auf den ersten Blick) monotone Umgebungen, in denen man sich leicht verirren kann. Aber just diese Gleichförmigkeit begünstigt die Erscheinung der Dämonen, der Gestalten des “großen Anderen”, der Engel und Genien.”

“He who sits alone and is quiet has escaped from three wars: hearing, speaking, seeing: but there is one thing against which he must continually fight: that is, his own heart.” (St.Anthony)

Macho designates these special cultural techniques with the word ‘loneliness-techniques‘:

“‘Einsamkeit’ soll als Titel für Prozesse figurieren, die aktiv initiiert und nicht erlitten werden; sie soll als eine zwar ambivalente, doch nicht nur schmerzliche, sondern auch lustvolle Erfahrung thematisiert werden; und sie soll als Kontext wie Anlaß der Praktizierung kultureller Techniken wahrgenommen werden, – gerade nicht als Pathosformel für kontingente Ereignisse oder fatale Umstände. (-) Worin bestehen die Techniken der Einsamkeit? Sie lassen sich ganz allgemein als “Verdoppelungstechniken”, als Strategien der Selbstwahrnehmung, charakterisieren. Wer nicht einfach bloß von allen Menschen verlassen wird (was gewöhnlich zum Tod führt), sondern seine “Verlassenheit” überlebt, bewältigt und gestaltet, inszeniert irgendeine Art von Beziehung zu sich selbst. Indem er seine Einsamkeit perzipiert, ohne verrückt zu werden, spaltet er sich zumindest in zwei Gestalten auf: als ein Wesen, das mit sich allein, – und daher eigentlich “zu zweit” – ist.”

«Einsamkeit “spricht”, sie beschwatzt und überredet, darin besteht ihre potentielle Schädlichkeit. Der Einsame läuft Gefahr, buchstäblich “zu Tode geredet” zu werden, – und zwar von sich selbst. (-) Denn wer allein ist, setzt sich zu vielen Stimmen aus: gleichgültig, ob er sie nun als eigene oder fremde Stimmen vernimmt.(-) Einsamkeitstechniken sind Strategien zur Initiierung und Kultivierung von Selbstwahrnehmungen (einschließlich der Imagination von Vorbildern und “Leitstimmen”); sie bezwecken eine Anregung und Disziplinierung – nicht aber die wahllose Entfesselung – innerer Dialoge.»

“Any man who is half-way decent will think himself extremely imperfect, but a religious man thinks himself wretched.” (CV , 1944)

That is similar to what Abreu and Neto is saying in their interesting paper ‘Facing up to Wittgenstein’s Diaries of Cambridge and Skjolden. Notes on Self-knowledge and Belief’. Wittgenstein’s diaries are in reality reports from the human war front, and they are as important or even more improtant for understanding his work as his more technical books and papers. Every human being is in his or her own way out there in the front line of living, fighting some visible or invisible human war. In this way there is always some war going on in every individual human mind. Some of us chooses to forget this fact; Wittgenstein did the opposite.

In the Skjolden notes from 15.3.1937 Wittgenstein is writing:

“Knowing one’s own self is dreadful because one knows at the same time the living demands, &, and one knows he is not satisfying it. However, there is no better way of

knowing oneself than to look for the Perfect. Therefore, the Perfect should awaken in men a tempest of resentment; if they do not want to feel completely humiliated. I believe the words Blessed, the one that is not angry with

me means: Blessed the one who withstands the vision of the Perfect.”

“I know that human beings on the average are not worth much anywhere.” /“Living with human beings is hard! Only they are not really human, but rather 1/4 animal and 3/4 human.”

“I had felt in his book (Tractatus) a flavour of mysticism, but was astonished when I found that he has become a complete mystic. He reads people like Kierkegaard and Angelus Silesius, and he seriously contemplates becoming a monk.”

“He has penetrated deep into mystical ways of thought and feeling, but I think (though he wouldn’t agree) that what he likes best in mysticism is its power to make him stop thinking.”

“What would one not give for a little depth”.

“Then during the war a curious thing happened. He went on duty to the town of Tarnov in Galicia, and happened to come upon a bookshop, which, however, seemed to contain nothing but picture postcards. However, he went inside and found that it contained just one book: Tolstoy on the Gospels. He brought it merely because there was no other. He read it and re-read it, and thenceforth had it always with him, under fire and at all times. But on the whole he likes Tolstoy less than Dostoyevsky (especially Karamazov). He has penetrated deep into mystical ways of thought and feeling, but I think (though he wouldn’t agree) that what he likes best in mysticism is its power to make him stop thinking. I don’t much think he will really become a monk — it is an idea, not an intention. His intention is to be a teacher. He gave all his money to his brothers and sisters, because he found earthly possessions a burden. I wish you had seen him.”

“Our civilization is characterized by the world progress. Progress is its form, it is not one of its properties that it makes progress. (…) Its activity is to construct a more and more complicated structure. And even clarity is only a means to this end & not an end in itself. For me on the contrary clarity, transparency,is an end in itself. I am not interested in erecting a building but in having the foundations of possible buildings transparently before me. So I am aiming at something different than are the scientists”.

“Of one thing I am certain. The religion of the future will have to be extremely ascetic, and by that I don’t mean just going without food and drink.”

“I am not a religious man but I cannot help seeing every problem from a religious point of view”.

“we have suffered a catastrophic loss of understanding of the need for self-awareness leading to widespread acedia. (-) Pre-modern European societies were often ignorant, poor and sometimes cruel, but they had a strong sense of the vital importance of the interior world of each human being. That interior world was the resource that enabled them to survive the horrors of their age. The interior world of human beings is a mixture of irrational and rational forces. The spiritual exercise of reason was the ancient and monastic response to this world, with daily reflection on the workings of my innermost soul; from such exercises flowed the solutions to life’s challenges and temptations. By contrast, in our culture, we are brought up without explicit and systematic spiritual formation, (-) we have a created a culture of spiritual carelessness that neglects the disciplined life of the soul. Spiritual carelessness seems (-) to underlie much contemporary unhappiness in Western culture. The word is no longer used not because the reality is obsolete but because we have stopped noticing it. We are too busy to be spiritually self-aware and our children grow up in a culture that suffers from collective acedia. Acedia has so established itself that it is now part of modernity.”

“There is part of me that wants to write my biography and indeed I would like to have it all laid out clearly both for myself and for others; not so much as to hold judgment over it, but merely to be honest and open about it.”

“Well, we are all such helpless failures in the last resort. The sanest and best of us are of one clay with lunatics and prison inmates, and death finally runs the robustest of us down”(VRE).

“whenever I have time now I read James’s Varieties of Religious Experience. This book does me a lot of good. I don’t mean to say that I will be a saint soon, but I am not sure that it does not improve me a little in a way in which I would like to improve very much; namely I think that it helps me to get rid of the Sorge”.

Malcolm wrote about him:

“In general, there is a striking contrast between the restlessness, the continual searching and changing, in Wittgenstein’s life and personality, and the perfection and elegance of his finished work.”

“his circles with language reveal themselves ethically grounded, his search for philosophical clarity as a search for clarity about himself.”

“Wittgenstein’s Diaries (-) are basically made out of these two self technologies (of self observation and confession). He begins the Diary of Cambridge by declaring that one need a bit of courage in order to write a reasonable observation about himself (-). And later on, in the Diary of Skjolden he writes: How hard is to know oneself, to confess honestly what one is.”

”sanctification is an inner process that reflects a spiritual transformation of the entire person….”

“Wittgenstein was a very singular man, and I doubt whether his disciples knew what manner of man he was.“ (B.Russel)” Every art, every philosophy may be viewed as a remedy and an aid in the service of growing and struggling life; they always presuppose suffering and sufferers. But there are two kinds of sufferers: . . . I now avail myself of this main distinction: I ask in every instance, “is it hunger or superabundance that has here become creative?” (Nietzsche)

“I remember him as an enigmatic, noncommunicating, perhaps rather depressed person who preferred the deck chair in his room to any social encounters.” (Dr E.G. Bywaters)

So alluring is Wittgenstein’s enigmatic figure that it stirred the american writer Bruce Duffy to create ‘The world as I found it’ (1987) ; a historical novel centered on Wittgenstein and his philosophical companions Russel and Moore.

So alluring is Wittgenstein’s enigmatic figure that it stirred the american writer Bruce Duffy to create ‘The world as I found it’ (1987) ; a historical novel centered on Wittgenstein and his philosophical companions Russel and Moore.For me as for many other ‘Wittgensteinoide’ persons, this double question plays a central role when it comes to understanding the rest of his philosophical thinking. This is a complex of questions that also is connected to his philosophy and his thinking. For Wittgenstein his thinking in philosophy all along and all the time was and must be part of how he tried to live as a human being…. so he tells in a personal note:

“How can I be a logician when I am not yet a man?”

“What is the use of studying philosophy if all that it does for you is to enable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., & if it does not improve your thinking about the important questions of everyday life, if it does not make you more conscientious than any . . . journalist in the use of the DANGEROUS phrases such people use for their own ends”.

“Ludwig Wittgenstein was undoubtedly a most uncommon man. Though he was free from that form of vanity which shows itself in a desire to seem different, it was inevitable that he should stand out sharply from his surroundings. It is probably true that he lived on the border of mental illness. A fear of being driven across it followed him throughout his life. But it would be wrong to say of his work that it had a morbid character. It is deeply original but not at all eccentric. It has the same naturalness, frankness, and freedom from all artificiality that was characteristic of him.” (From Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir (London: Oxford University Press, 1958), p3)

“Wittgenstein was a tormented and paradoxical figure. A central European of nouveau riche background and aristocratic outlook, of mixed religion, with a well-founded fear of madness, a leaning toward suicide, sexually uncomfortable, a high stylist with a taste and gift for aphorism, widely cultured but uninterested in and unimpressed by learning, almost a human embodiment of the fascinatingly disintegrating city and empire of his birth, he becomes a professor, an academic in the most complacent city in generally complacent England, the most philistine of major European nations. Hoping to change men’s lives, he writes about the highest logical and semantic abstractions, and leaves behind not saved souls but decent academic functionaries who occupy a crucial position in the industry of explaining his works so that they are suitable for purposes of teaching and examination. It was an ironic situation, the attempt of an eagle to make a career in a cuckoo clock.” (Anthony Quinton, Essays. Manchester, England: Carcanet, 1998, p.356)

‘Getting to know Wittgenstein was one of the most exciting intellectual adventures of my life’.

“Every great philosophy so far has been . . . the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir” (Nietzsche)

The leading voice of Logical Positivism, Rudolp Carnap, saw early on that Wittgenstein’s thinking was moving in broader spheres:

‘All of us in the Circle had a lively interest in science and mathematics. In contrast to this, Wittgenstein seemed to look upon these fields with an attitude of indifference and sometimes even with contempt.’

“is trying to get his reader to think of how the words are tied up with human life, with patterns of response, in thought and action. His conceptual studies are a kind of anthropology. His descriptions of the human forms of life on which our concepts are based make us aware of the kind of creature we are.”

It seems at the same time that Wittgenstein is trying to tell and show us something very important also through his immediate way of living and his reflections on his own personal life – something that most of us today have problems with getting in contact with and often cannot grasp.

In the book ‘Fat friday. Wittgenstein on aspects‘ (2010), the author John Verdi says this on Wittgensteins way of doing philosophy:

“Wittgenstein also believed that a serious philosophical work could be written that consisted of nothing but questions. His Philosophical Investigations contains 784 questions, of which only 110 are answered—and 70 of those answers are meant to be wrong! The questions, including those with wrong answers, challenge readers to think for themselves, which Wittgenstein believed was the only way we can come to see how language misleads us when it is not left alone to do its ordinary work. Wittgenstein’s style is dialectical, in the Socratic sense.”

A central problem in Wittgensteins thinking was – ‘what is it for a proposition to say something?’ The answer Wittgenstein gave in the Tractatus – ‘the correct method in philosophy would really be the following: to say nothing except what can be said’ – is one he later summarised as follows: ‘The individual words of language name objects—sentences are combinations of such names’ (PI§1).

‘One name stands for one thing, another for another thing, and they are combined with one another. In this way the whole group—like a tableau vivant—presents a state of affairs’ (TLP, 4.0311)

In the 1930s, Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language was dramatically transformed – he now tells that the meaning of a word is its use in the language; and that words can be used in many different ways, for an indefinitely broad and heterogeneous range of purposes. The picture of language in Tractatus is now seen, not as wrong, but as overly narrow, as Wittgenstein himself writes – it is

‘“appropriate, but only for this narrowly cirmcumscribed region, not for the whole of what you were claiming to describe”

“Philosophical activity is hermeneutical, it does not consist in logical analysis, but in description of human ‘language-games’”

‘a radical break with the idea that language always functions in one way, always serves the same purpose: to convey thoughts—which may be about houses, pains, good and evil, or anything else you please’ (PI).

“In philosophy matters are not simple enough for us to say ..Let’s get a rough idea,’ for we do not know the country except by knowing the connections between the roads. So I suggest repetition as a means of surveying the connections.”

“Language sets everyone the same traps; it is an immense network of easily accessible wrong turnings. And so we watch one man after another walking down the same paths and we know in advance where he will branch off, where walk straight on without noticing the side turning, etc. etc. What I have to do then is erect signposts at all the junctions where there are wrong turnings so as to help people past the danger points.”...…

But serious philosophical reflection is not easily made part of the ordinary affairs of everyday living;

“I sit with a philosopher in a garden; he says again and again ‘I know that that is a tree,’ pointing to a tree that is near us. A second man comes by and hears this, and I tell him: ‘This man isn’t insane: we’re just doing philosophy.”

“What is the use of studying philosophy if all that it does for you is to enable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., and if it does not improve your thinking about the important questions of everyday life?”

“Most propositions and questions which have been written about philosophical matters are not false, but senseless. We cannot, therefore, answer questions of this kind at all, but only state their senselessness. Most questions and propositions of the philosophers

result from the fact that we do not understand the logic of our language. (They are of the same kind as the question whether the Good is more or less identical than the Beautiful.) And so it is not to be wondered at that the deepest problems are really not problems.”(4.003)

“I might say: if the place I want to get to could only be reached by a ladder, I would give up trying to get there. For the place I really have to get to is a place I must already be at now. Anything that I might reach by climbing a ladder does not interest me.”…..

He tells about his Tractatus:……

“On the other hand the truth of the thoughts that are here communicated seems to me unassailable and definitive. I therefore believe myself to have found, on all essential points, the final solution of the problems. And if I am not mistaken in this belief, then the second thing in which this work consists is that it shows how little is achieved when these problem are solved.” (L.W. Vienna, 1918).

“Seventeen people are mentioned in the Investigations, among them Beethoven, Schubert, and Goethe; the Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Küohler; and the physicist Michael Faraday. Five others are mentioned twice — Lewis Carroll, Moses, and three philosophers: Wittgenstein’s Cambridge colleagues Frank Ramsey and Bertrand Russell, and Socrates. The three remaining people named in the Investigations are also philosophers: Gottlob Frege and William James, each mentioned four times, with only St. Augustine exceeding them with five citations” (Goodman 2002)

.”eg har opplevd mye liding, men eg er åpenbart ikkje i stand til å læra av livet mitt. Eg lid framdleis på akkurat same måten som eg leid for mange år sidan. Eg har ikkje blitt korkje sterkare eller klokare’.

Wittgenstein was most of his life occupied both with his own lived religious beliefs, and with philosophical discussions of religion. In his thoughts on religion it is easy to find traces of his basic anthropological ideas, that both humans and the world are ‘strange’; and his views on the secondary role of reason, rationality and science in human affairs and life.

1. sept. 1914 he started to read a book on religion by Leo Tolstoj. He tells that this book saved his life during the demanding years in the war. He had this book always with him through those years of hardship and in company with death. Many philosophers do not see Wittgensteins relation to religion as a central aspect of his philosophy.It is often regarded more as part of his personality difficulties than a philosophical matter. For Wittgenstein himself religion, belief, sins and virtues and his continous working on himself is central aspects of his thinking. As his sayd about Tractatus:

“the point of the book is ethical. I once wanted to give a few words in the foreword which now actually are not in it, which, however, I’ll write to you now because they might be a key for you: I wanted to write that my work consists of two parts: of the one which is here, and of everything I have not written. And precisely this second part is the important one. For the Ethical is delimited from within, as it were by my book; and I’m convinced that, strictly speaking, it can ONLY be delimited in this way. In brief, I think: All of that which many are babbling I have defined in my book by remaining silent about it. ” (Letter to Ludwig von Ficker,1919 (translated by Ray Monk)

“My work consists of two parts: the one presented here plus all that I have not written. And it is precisely this second part that is the important one. My book draws limits to the sphere of the ethical from the inside as it were, and I am convinced that this is the ONLY rigorous way of drawing those limits. In short, I believe that where many others today are just gassing, I have managed in my book to put everything firmly into place by being silent about it”…….

“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen”/”Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”

‘What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence’

‘There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical’ (Tractatus 6.522)…

“I can say: “Thank these bees for their honey as though they were kind people who have prepared it for you”; that is intelligible and describes how I should like you to conduct yourself. But I cannot say: “Thank them because, look, how kind they are!”–since the next moment they may sting you”.

“I have no religion, except perhaps this: that when things go well for me, I tell myself they don’t have to.”

“In recent years we have seen a widespread regression to pre-Wittgensteinian attitudes and ways of doing philosophy, in which the tendencies he regarded as unwholesome are given full rein.” (Oswald Hanfling, Wittgenstein and the Human Form of Life)

Litterature and references:

Culture and Value, by Gerd Brand, Robert E. Innis, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein : A Memoir . by Ludwig Wittgenstein , Cyril Barret, Yorick Smythies, Rush Rhees, James Taylor

Allen, Richard and Malcolm Turvey (eds.), Allen, Richard and Malcolm Turvey (eds.), Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts, Routledge, 2001, Routledge, 2001

Biletzki, Anat, (Over)Interpreting Wittgenstein, Kluwer, 2003

James R. Atkinson, The Mystical in Wittgenstein’s Early Writings, Routledge, 2009

Flowers, F.(ed.) ; Portraits of Wittgenstein, vol. 2, Bristol:

Thoemmes Press, 1999

Bouwsma, O. K. 1986 Wittgenstein: Conversations, 1949-1951, Indianapolis, Indiana: Hacket.

John W. Cook; The Undiscovered Wittgenstein: The Twentieth Century’s Most misunderstood Philosopher. New York: Prometheus Books

Crary, Alice and Rupert Read (eds.). 2000. The New Wittgenstein. London & New York: Routledge.

Alice Crary (ed.), Wittgenstein and the Moral Life: Essays in Honor of Cora Diamond, MIT Press, 2007

Drury, M. O’C. 1973 The Danger of Words, London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

Jesús Padilla Gálvez (ed.), Philosophical Anthropology: Wittgenstein’s Perspective, Ontos, 2010

GRASSL, W; and SMITH, B; A Theory of Austria. I

Garry L. Hagberg, Describing Ourselves: Wittgenstein and Autobiographical Consciousness, Oxford UP, 2008

Hacker, P. M. S. 2003. “Wittgenstein, Carnap and the New American Wittgensteinians”, Philosophical Quarterly53: 1-23.

Oswald Hanfling, Wittgenstein and the Human Form of Life

David Kishik, Wittgenstein’s Form of Life, Continuum, 2008

Klagge, James C., ed., Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, 2001

James C. Klagge; “Wittgenstein in Exile“, in: D.Z. Phillips, Macmillan, ed., Religion and Wittgenstein’s Legacy.

James C. Klagge, Wittgenstein in Exile, MIT Press, 2011

Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir, Oxford University Press, London, 1977

McGuinness, Brian; Approaches to Wittgenstein: Collected Papers. London: Routledge, 2002

McGuinness, Brian; Wittgenstein: A Life, Young Ludwig (1889-1921), Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988

Ray Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, The Free Press, New York, 1990

Russell Nieli, Wittgenstein: From Mysticism to Ordinary Language, State University of New York Press, Albany, New York, 1987

Russell Nieli; ”Mysticism, Morality, and the Wittgenstein Problem,” Archiv für Religionsgeschichte, 9(2007):83-141.

Nyíri, J.C. (ed.): From Bolzano to Wittgenstein. The Tradition of Austrian Philosophy. Vienna: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986

OXAAL, Ivar. On the Trail to Wittgenstein’s Hut: The Historical Background to the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers

Pinsent, David H., A portrait of Wittgenstein as a young man: from the diary of David Hume Pinsent, 1912-1914, G.H. von Wright (ed.), Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1990.

Anthony Quinton, Essays. Manchester, England: Carcanet, 1998

Rush Rhees, editor, Recollections of Wittgenstein, Oxford University Press, New York, 1984

Somavilla, I. 1997 “Vorwort”, in L. Wittgenstein, Denkbewegungen:

Tagebücher 1930-1932, 1936-1937, Innsbruck: Haymon-Verlag.

Ginia Schönbaumsfeld, A Confusion of the Spheres: Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein on Philosophy and Religion, Oxford University Press, 2007

Wittgenstein, L. 1997 Denkbewegungen: Tagebücher 1930-1932,1936-1937, Innsbruck: Haymon-Verlag.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1980. Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology, Vol I. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Wittgenstein’s Lecture on Ethics,” Philosophical Review, 74(1965):3-12.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Notebooks 1914-1916, edited by G.H. von Wright and G.E.M. Anscombe, with English translation by G.E.M. Anscombe, Harper and Row, New York, 1961.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, translated by D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness, Humanities Press, New York, 1961.

Other internet based sources

- Cambridge Wittgenstein Archive German and English, includes pictures, biography, searchable database of manuscripts.

- Wittgenstein Portal The Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein: Background Retrieved March 22, 2007. An excellent on-line biography, including a running account of his manuscripts.

- The Wittgenstein Archives, University of Bergen.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) This is a comprehensive resource of Wittgensteinian material.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario