|

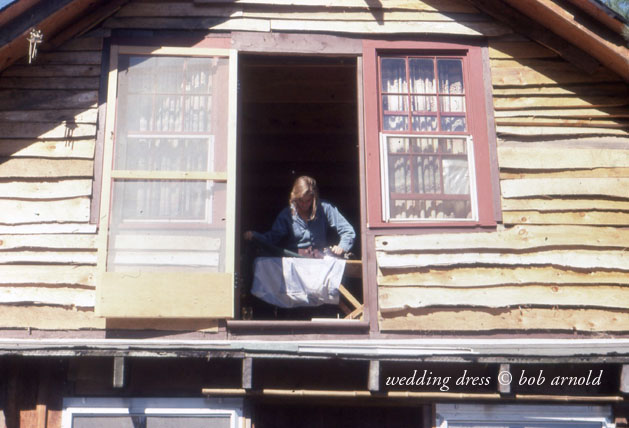

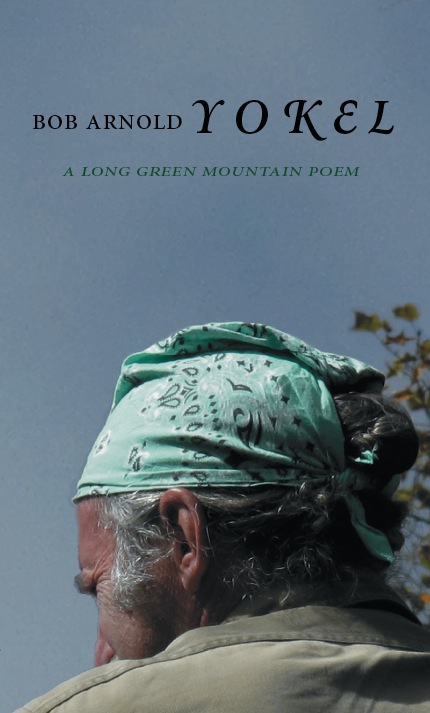

| Photo copyright © Susan Arnold, 2006 |

I have very little to write about until I’m out in life living it. This means with the chainsaws, the hammers, the stonework, the woods, the fields, the river, and with the girl, Susan. It’s been that way for almost 40 years and I’m doing everything within my powers to make sure it doesn’t stop. Even if a lot of the time it seems fueled on a dream, gritty determination and the greatest thing that ever hit town, team-work. I can’t say enough for love and marriage. And I know that thought is going to make some smile, and make others grimace...I think the key is staying loose, eyes open, available and even vulnerable, open for a pass. It’s downright athletic. After a life of cutting trees, roofing homes, huts and barns, cribbing up old shacks and cabins and houses, painting and painting, raking and raking, wood-splitting & wood-splitting, the body and the mind get to know one another. If you develop the mind along with the body, it could become a lantern burning bright.Of course I must tip my cap to my background — a flinty Irish mother from Belfast with a large family of storytellers and hard workers, lots of kids. And on my father’s side, all lumbermen, mainly businessmen when I was born, but all the forefathers were choppers, sawyers, drivers, mountain butchers. The businessmen wanted the oldest son, me, to learn the ropes, so I was dropped into the lumberyards at age ten and worked every day after school with more Irishman and Poles and all through each summer — first unloading boxcars of western and eastern lumber and loading truck deliveries, and then when I was a little older, receiving those truck deliveries on some muddy hillside with a carpentry crew and two or three spec houses going up. The plan was to teach me the business and then after college go into the business. Put on a tie. Instead, the sixties got in the way, with its music and rebellion and tribal strength, and I barely got out of high school.

It hardly mattered what time of year

We passed their farmhouse,

They never waved,

This old farm couple

Usually bent over in the vegetable garden

Or walking by the muddy dooryard

Between house and red-weathered barn.

They would look up, see who was passing,

Then look back down, ignorant to the event.

We would always wave nonetheless,

Before you dropped me off at work

Further up on the hill,

Toolbox rattling in the backseat,

And then again on the way home

Later in the day, the pale sunlight

High up in their pasture,

Our arms out the window,

Cooling ourselves.

And it was that one midsummer evening

We drove past and caught them sitting

together on the front porch

At ease, chores done,

The tangle of cats and kittens

Cleaning themselves of fresh spilled milk

On the barn door ramp;

We drove by and they looked up—

The first time I've ever seen their

Hands free of any work,

No too or rope or pail—

And they waved.

Bob Arnold and his wife Susan oversee Longhouse Press with a mission to produce books of poetry to the highest standards of craftsmanship. For over thirty years they have stewarded the work of an extraordinary range of poets from America and beyond, as well as serving an integral role in continuing the mission of their close friend Cid Corman's journal Origin. In addition to this work, Mr. Arnold is literary executor both for Mr. Corman and (after Corman's passing) Lorine Niedecker. Thus, a tremendous amount of artistic energy is cultivated on the grounds of the Arnold's Vermont farm.

I’ve just completed a 105 piece long poem called Yokel that took ten years to write. It’s farm narrative and portraits and outdoor work poems covering four decades of watching this old life and tradition around me disappear from the map. It just couldn’t be done with small poems only — just as Basho’s travel notebook had to be pinpoint poems compassed around a netting of anecdotes and ruminations. My long poem Yokel has big brawny pieces wide as the barn door and a river sounding endless to the ears. It takes the architecture of a long poem to carry that span.

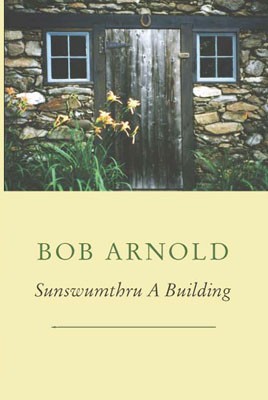

Picking up where Bob Arnold's earlier book On Stone: a builder's notebook left off, Sunswumthu A Building is a series of brief, concise prose meditations on tools, carpentry, masonry and life in the Vermont woods, far removed from our digitally accelerated society with its increasingly shorter attention spans. Arnold writes with the keen eye and careful consideration of a postmodern Thoreau-his powers of observation and ability to zoom in on the underlying aesthetics of a splitting maul, wheelbarrow, or even a simple hammer can be read as parables for distilling the inherent metaphysics from any given implement or situation

~ Mark Terrill / Rain Taxi

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario