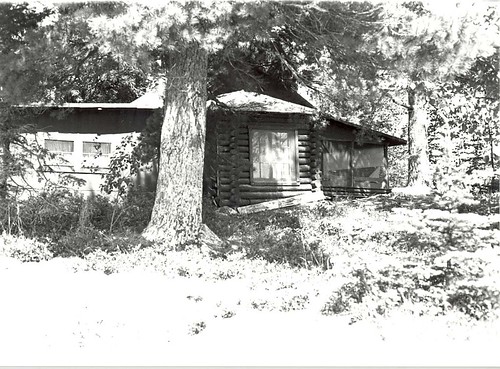

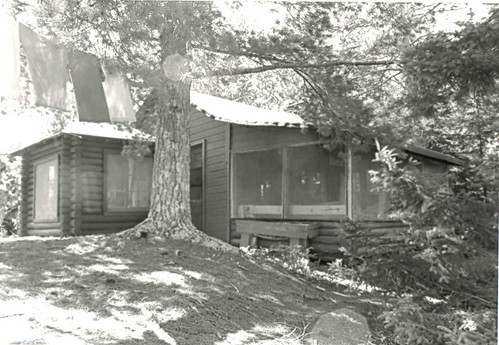

Fujita built his Rainy Lake cabin in the border lakes region of Minnesota, near the Canadian border, shortly after the land was purchased. Marked by their simplicity, his rustic wooden one-room cabin and its setting are evocative of both the architecture and landscapes of Japan. The natural materials, minimal decoration, side entrance, moderate pitched roof, veranda, and lack of foundation are all typical features of modest residential Japanese construction. The cabin is integrated into the surrounding forested landscape: the floor to ceiling windows to give extensive views of the natural rock around the house, and of the lake, which provided an atmosphere conducive to reflection. Jun Fujita (1888-1963) was one of the earliest Japanese-Americans to achieve prominence in the Midwest. A noted photographer and poet in the first half of the 20th century, Fujita used his rustic cabin on a remote island near Ranier, Minnesota (now within

Voyageurs National Park), as a retreat and a source of inspiration for his artistic work. Fujita left his native Hiroshima as a teenager and immigrated to Canada, where he may have first begun his career as a news photographer. Sometime before 1915, he moved to Chicago where he worked with the Evening Post until at least 1929, before he turned to commercial and artistic photography. A consummate artist who moved easily between visual and verbal media, Fujita was inspired by the natural world, and his poetry, paintings and photography are dominated by images of flowers, forests and landscapes. Some of his color photos of flowers are in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago; and during the 1920s, many of his poems--in haiku and tanka, a minimalist Japanese form--were published in the prestigious literary serial, Poetry. His poetry was unusual in that it applied the rules of Japanese poetic genres to poetry written in English well before the vogue of English haiku. Land for Fujita's cabin was purchased by Florence Carr in 1928. Fujita and Carr, a Euro-American secretary and social worker, had a long-term relationship and were living together in Chicago at that time. Carr purchased the property because of Minnesota state laws that restricted the land ownership of Asian aliens. They eventually married in 1940, in part to protect their mutual property in several different states. Carr did not accompany Fujita on his many retreats to the cabin which he used until 1941, shortly before America entered World War II. Fujita was able to avoid wartime internment by residing in Chicago, and chose instead to retreat to a cabin in Indiana just an hour from the city.

Fujita's success as a photographer working for a mainstream newspaper and for major commercial corporations was extremely unusual among Japanese-Americans in his time, and especially among the Japanese-born population. That he achieved this success in the Midwest is even more noteworthy. Census figures from the 1940s show that fewer than 5 percent of the Japanese-American population in the U.S. lived outside of Hawaii and the West Coast states. Strict immigration laws of the time made it difficult even for someone as successful as Fujita to naturalize. It was only through a private congressional bill in 1954 that Fujita finally became a U.S. citizen.

(http://www.hermitary.com/articles/fujita.htm)

Jun Fujita was born December 13, 1888 near Hiroshima. He was a photographer at the Chicago Evening Post -- the only Japanese newspaper photographer in the U.S. at that time. After he left Chicago Post (around 1929) he started his own commercial photography business. In 1935 and 1936 he was commissioned by the U.S. to photograph Federal Works projects throughout the states. Some of his photographs can be found in the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. His first and only collection of tanka poetry was published in 1923: Tanka: Poems in Exile. He also painted watercolors and sketched.

When I found out that Fujita had a log cabin in the boundary waters between Minnesota and Canada on Rainy Lake, I became obsessed with planning a journey there, especially since 2008 is the 120th anniversary of his birth. Through the help of Mary Ann Woods-Kasich the proprietress of WordsPort Cottages in Rainer, I found a guide who knew where the cabin was -- the exceptionally informative Dock Holiday (Bill Genell) of Dock Holiday Services.

The poet's cabin (30 miles east of Rainier, Minnesota) is a registered historical site; it lies nestled among ancient granite outcroppings which the last glacier deposited. The cabin faces northeast and the only sound you can hear is the lake lapping against the island's flat rocks.

the poet's cabin

how pine trees emerge

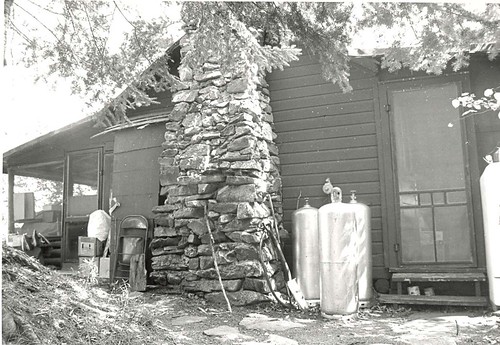

from deep in the rockWe dock on the southwest end of the island and walk through a circuitous route of fallen pine and overgrown ground cover. It truly feels as if we have walked back in time or time -- in an instant -- has stopped. The first thing you notice as you approach the north side of the cabin is a beautifully crafted chimney; at intervals the chimney has stone ledges imbedded strategically for easy climbing.

my feet finding

the old path to the cabin

this summer's dayFacing the lake is an old log bench fragile and covered with moss. The poet's bench has become part of the woods once again. The peat moss underfoot is soft and buoyant; as you walk upon it the scent of very old layers of pine needles, earth and leaves rise up. Surrounding the cabin is a deep ring of wild blueberries there for the picking.

on the island

wild blueberries surrounding

the poet's cabin

Though we were prohibited from going inside the cabin, one can peek in through the windows. The first thing that calls your attention is the elevated dining area surrounded by low windows. One could imagine Fujita kneeling on a mat and eating or writing at a low table with the lake surrounding him on all sides. The dining area is a sort of lighthouse focal point which the lake and the sky circle around.

at Rainy Lake

the old log bench

letting the light through

The second thing that you notice is how finely crafted the pine wood joints are -- cut and placed just right. Then the fireplace and hearth capture your attention for it is the fireplace which holds the magic stones of an ancient glacier. These are power rocks which Native Americans believe were filled with an almost audible memory; magically they can hold the spirit of the poet who lived here for a time. The stones chant to us of Fujita's presence, now gone but always felt in the little island cabin, this poet's retreat.

The stones chant to us as well of the ages gone by where there was only one endless bed of glacier covering a desolate earth, but in a second, in the blink of an eye, gone, Fujita gone, too, and soon, too soon, all of us. You can feel the spirit of Fujita surrounding just as the ancient lake surrounds the island.

the motion of the trees

and the motion of the lake

in and out of time

We go to the porch and imagine how he would have perhaps slept out there on a warm summer's night -- the blackness of the lake shifting and quaking under the island's rocks while the island itself rises and falls as if it were breathing in unison with the sleeper's dreams deep into the night.

out of the woods --

the way the cabin

collects light

Only one other person, the guide tells me, in the past five years has sought out this cabin. Fujita's spirit has infected us both with a longing to see and touch what he saw, what he touched; we do it in order to feel our spirits fill with wonder, recognition and communion. We do it to heal. Suddenly I notice in the dining area a talisman hanging from a leather string; it could be a crude dream catcher or it could be a charm to ward off evil spirits -- either way, I feel the poet's cabin, as well as the poet's spirit, are safe and secured from any harm. In a strange way, part of this charm touches me deeply as well.

As we boat away from the island two birds -- seagulls I think -- flirt with the air currents circling above the cabin. Later we see two white-tailed deer frolicking in the waters of the lake by the shoreline. Behind the sound of the motorboat a deep quietness realigns itself and enters my heart. I have seen what he saw; I have touched what was his. Can this ever be erased?

leaving the island

it could be lake spray

in my eyes

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario