At the time, he was also a house-husband, he said, with a young son and a daughter, and was working his way alone through the building process. Fired up by the Foxfire books, the how-to guides for the ’70s-era back-to-the-land movement, he would pore over the pages, practicing dovetails until he was pitch-perfect.

“I didn’t know much about building, and I was intimidated by people that did,” he said. “Also, I wanted to face the problems myself. It was a passage, finding my way through a house and into a life. It was a real quest.”

At 36, he went back to school, straight into the graduate art program at the University of North Carolin

a, 10 minutes away. His first stick work, a man-size tangle of saplings made on a picnic table at home, startled his professors, he said. They thought “it was too complete for someone who’d been blundering around in the netherworld.”

Since then, he has made well over 200 startling (and delightful) pieces for sites all over the world — woolly lairs and wild follies, gigantic snares, nests and cocoons, some woven into groves of trees, others lashed around buildings. And in August, he was invited by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to make a piece for its centennial: you’ll find “Natural History,” five winsome wind-blown pods that Mr. Dougherty described as “lairs for feral children or wayward adults,” near the Magnolia Plaza there.

Thirty-eight of these works are collected in “Stickwork,” a monograph-memoir, published last month by Princeton Architectural Press. It’s full of installation tales, like the time he camped in a Japanese temple while working on a piece and was warned by his host about the poisonous but sacred snakes that lurked there. “Don’t kill them,” Mr. Dougherty recalled the host saying. “If one bites you, call my wife and she will take you to the hospital.”

Mr. Dougherty is a very good storyteller. And there is always a story, because each piece takes at least three weeks to make, blooms before a rapt and sometimes fractious audience, and depends on the efforts of a fresh team of volunteers new to stickwork, over which Mr. Dougherty presides like an enthusiastic Outward Bound leader.

“It’s a problem-solving event, and problems arise every day,” he said. “You have to be flexible. I like working with sticks, but it’s really an excuse to have these experiences. One is to be bad and play out some kind of stick thing in a public place, like pulling your pants down, and another is this huge outpouring from people who don’t know you and walk up to you and say, ‘What is this?’ ”

The book chronicles Mr. Dougherty’s stunning output of nine works a year, every year. What it doesn’t reveal are the ways in which Mr. Dougherty and his family cope with his unrelenting schedule, and how a simple house can be a staging ground for a career.

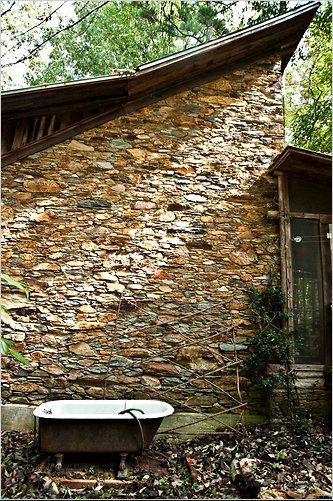

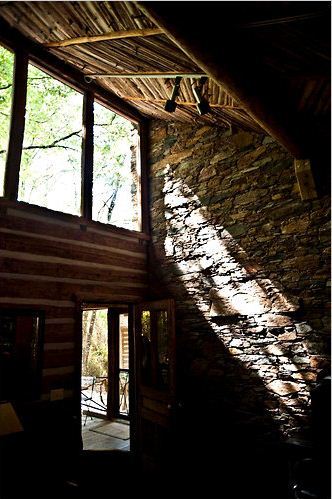

“The cabin is pretty self-sufficient,” he said (taxes are $1,100 a year). “It has stood by me, been my cohort. There’s no rent to pay, and it’s been a good place to come home and store my stuff. It’s also a place to work ideas out. It became central to my imagining my life as a sculptor.”

Certainly the log house is as compelling and artful as one of his sculptures. Ceilings are veneered with sticks laid out in a herringbone pattern. A deer fence is like tough woodland lace. There is a small herd of outbuildings, the sides of which are layered with Mr. Dougherty’s experiments in cladding; one of them looks as if it’s lined with feathers.(...)

By PENELOPE GREEN (Fuente: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/07/garden/07twig.html)

A version of this article appeared in print on October 7, 2010, on page D1 of the New York edition.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario