Highlights of a Life

Alix Kates was born August 17, 1932, in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. She was the daughter of an upper-middle class couple; her father, Samuel, was an attorney and labor arbitrator, her mother, Dorothy, was an aspiring writer and feminist activist. Her parents had already adopted her cousin, Robert, when his mother died in childbirth. A maid served the family dinner every night in their comfortable, Shaker Heights home. Alix had music lessons and play dates as a child, and in high school she couldn’t get enough of cashmere sweater sets.

Alix would eventually denounce this bourgeois upbringing and separate herself as much as possible from her parents and her childhood. But immediately after high school, she was not yet ready to leave. She attended Case Western Reserve’s Flora Stone Mather College in Cleveland, where she studied history and philosophy and graduated in three years, in 1953.

Graduate school at Columbia, in New York, was Alix’s ticket to escape. “I knew I would suffocate if I didn’t leave,” Alix would write in her 1999 memoir, A Good Enough Daughter. “I thought that freedom required my leaving behind the one life I’d ever known,” she said in the Spring 1999 Ohioana Quarterly. “After that… I seldom looked back, restricting my contact to the occasional phone call, the holiday greeting, the annual visit. My parents, involved in their own dense lives, let me go, but were always there for me when I needed them.”

At Columbia, Alix studied mathematics and philosophy, then male-dominated fields. In the CWRU Magazine, Summer 1999, she says, “Math was an impossible field for women then. Even philosophy was impossible. Who would have given me a job?” The inevitability of failure for a woman in these pursuits eventually wore Alix down. She married Marcus Klein, a graduate student in the English department, quit school after two years, and worked as a receptionist, researcher, and encyclopedia editor to support her husband.

This first marriage didn’t last, and Alix married again in 1959, to Martin Shulman, with whom she would have two children, Theodore and Polly. Alix’s children helped her to give birth to a writing career, after she read to them and realized she could write a children’s book to earn some money. She succeeded with Bosley on the Number Line, a book about math concepts for children, published in 1970.

By this time Alix had already gotten involved with the “heady” leftist political and feminist movements of the 1960s. In a 1997 Ms. magazine interview she said, “The minute I heard feminism articulated, I recognized it as an explanation of all my puzzles.” She participated in consciousness-raising groups where “women shared their frustrations with marriage, male infidelities and insensitivities, and educational and professional limitations for women” (CWRU, 18). She told The Plain Dealer May 26, 1998, “The main way in which we learned about the true conditions of women was by talking honestly to each other, to try and understand what had been hidden by ruthlessly and honestly examining our own lives.” Her next children’s book was To The Barricades, a biography of Emma Goldman, anarchist and free-love feminist of the late nineteenth century.

In her article “For Love and Money: The Politics of Solitude,” published in Poets & Writers Magazine, January/February 1996, Alix says:

When I first started writing—which I did partly out of a passion to spread the new feminist ideas, partly out of ambition, and partly for sheer love of the process—the only time I had to myself were the three hours a day my children were in nursery school... It took a tremendous amount of love of the work and faith that something might eventually come of it to pull off even that amount of solitude. (And now I learn that my children, who are now both professionals in their thirties, believe in retrospect that when they were growing up my work meant more to me than they did, whereas I, at the time, thought I was giving them the tremendous gift of a mother who, rather than live through her children, had work that I cared about passionately, as well as a stay-at-home life that left me always available for them…)

In Publishers Weekly, June 5, 1972, Shulman said, “I began by taking the phone off the hook the moment the kids left for school and in time I got up the nerve to leave it off until they came home.

If you want to know what took raw courage, it was closing the door of the room in which I work: The notion of a woman typing at home may not be radical, but typing with the door shut? It blew the family’s collective mind, and it was one of the most liberating experiences of my life…”

In 1969, Alix had done enough writing behind closed doors to publish the article “A Marriage Agreement,” a proposal that a married man and woman split their housework and childcare equally. In “For Love and Money,” she writes, “At the time the idea was so outrageous that my piece was reprinted widely, in New York magazine, Ms., Redbook (where it received more reader letters than any other article Redbook had ever published), and, in 1972, Life magazine, where it was the subject of a six-page spread.”

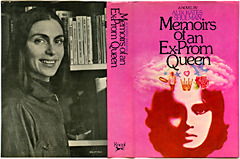

The publicity generated from this article could be part of what caused a kind of “bidding war” over the rights to print paperback versions of her astonishingly successful 1972 first novel, Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen. The novel is called a “breakthrough book” for the feminist movement, but Alix described it to Contemporary Authors as a “comic novel about coming of age in the fifties.” Sasha Davis, the protagonist, is “a white, middle-class midwestern girl… who grows to womanhood trying to be everything an ideal woman was expected to be before the women's movement--sexy prom queen, beautiful wife, devoted mother. But nothing works out as expected.”

The Plain Dealer, Tuesday, May 26, 1998, called Memoirs a “devastating portrayal of an era that, Shulman made clear, cheated women by focusing only on their appearance and their ability to catch a man.” In the same article, Shulman explains the discrepancy between the happy childhood and teenage years she spent in Cleveland, and the biting cynicism with which she wrote the book. “I wasn’t thinking then what Sasha was thinking… It wasn’t until my own consciousness was raised through the women’s movement that I was able to get a perspective on it.”

The novel that followed was Burning Questions, in 1978, which she describes as “the story of another kind of woman, a self-styled rebel whose political awakening in the late sixties transforms her. At once a political and historical novel, spanning four decades... Burning Questions attempts to portray the important changes in women's lives and consciousness wrought by contemporary feminism.”

On the Stroll was Shulman’s third novel, published in 1981, a departure from her earlier subjects. “The Stroll” is the nickname for the portion of New York’s Eighth Avenue where pimps recruit young women to be prostitutes. Its main characters are a bag lady, a 16-year-old runaway girl, and the pimp who becomes involved with her. The book earned accolades for its content and style, and for Shulman’s daring in trying a different kind of subject matter.

In 1982, Shulman dared herself to go even further from her comfort zone. At fifty, she “left a city life dense with political activism, family, and literary community, and went to live alone on an island off the Maine coast. On a windswept beach, in a cabin with no plumbing, power, or telephone, she found to her astonishment that she was learning to live all over again, discovering capacities for thought, feeling, and sensual delight that she had never imagined” (Drinking the Rain press release).

With this time alone to write, and her 25-year marriage ending in divorce, Alix Kates Shulman published her fourth novel, In Every Woman’s Life, in 1987. Contemporary Authors describes the book as follows: “The title refers to the premise that every woman, at some point in life, must think about marriage. The novel focuses on three women: Rosemary Streeter, a successful New York professional/wife/mother who, in the author's words, ‘has made-do’ in a long-lasting marriage; Nora Kennedy, something of a foil for Rosemary, a journalist, single, and opposed to marriage but involved in an affair with a married man; and Rosemary’s daughter, Daisy, who ‘must still decide how to live,’ in Shulman's words.”

In 1989 Alix married again, this time to Scott York. She continued to escape to Maine during summers, finding ways to integrate the awareness that solitary, quiet life taught her into her active, hectic city life. Shulman turned these summer experiences into a 1995 memoir, Drinking the Rain. The book’s press release says this about it:

Drinking the Rain is far more than a paean to the pleasures of foraging for wild greens or intertidal shellfish and cooking them in delicious new ways, of developing a sense for environmentally sound, low-tech thrift, of coming to terms with changes wrought by aging, by new love affairs, by ecological or nuclear disasters. Over the course of an unsettling divorce, a sojourn in the New Age mountains of Colorado and Chernobyl—she came to find true spiritual discipline and liberation. Her book is a literary triumph on that theme, from the pen of a keenly observant, highly focused, skeptical woman who is contagiously delighted with life and dedicated to its betterment.

In 1996, both of Alix Kates Shulman’s parents died (her father was 95 and her mother 89). Six years earlier, she had begun returning to Cleveland to care for them and their estate, in their failing health. At first she resisted “going home” after being free for so long, but once the journey began, she found it wonderful to reconnect with her roots, her parents, and herself. She discovered things about her parents which she didn’t notice as child – their activism, their love for language, and their feminism – things which were crucial parts of Alix Kates Shulman’s identity. She wrote in the Ohioana Quarterly, “As a child I was a good daughter, as an adolescent a bad one, and as an adult a thoughtless one. But having come through for my parents in the end, I think that in sum, as I have titled my book, I was A Good Enough Daughter.” This memoir was published in 1999.

While examining her parents’ house, letters, and memorabilia, Alix discovered things about her adopted brother and what that adoption meant to the family, and found it interesting enough to serve as fodder for a new novel. When this novel is finished, as hopefully it will be soon, it will likely be similar to the rest of Shulman’s novels: witty, realistic, insightful, and life-affirming.

(OHIOANA Authors). (

http://www.ohioana-authors.org/shulman/highlights.php#top)

At fifty, Alix Kates Shulman left a city life dense with political activism, family, and literary community, and went to stay alone in a small cabin on an island off the Maine coast. Living without plumbing, electricity, or a telephone, she discovered in herself a new independence and a growing sense of oneness with the world that redefined her notions of waste, time, necessity, and pleasure. With wit, lyricism, and fearless honesty, Shulman describes a quest that speaks to us all: to build a new life of creativity and spirituality, self-reliance and self-fulfillment.

At fifty, Alix Kates Shulman left a city life dense with political activism, family, and literary community, and went to stay alone in a small cabin on an island off the Maine coast. Living without plumbing, electricity, or a telephone, she discovered in herself a new independence and a growing sense of oneness with the world that redefined her notions of waste, time, necessity, and pleasure. With wit, lyricism, and fearless honesty, Shulman describes a quest that speaks to us all: to build a new life of creativity and spirituality, self-reliance and self-fulfillment.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario