(1937-2005)

En “La Gran Caza Del Tiburón” (1979) fue requerido por la revista “Playboy” para hacer un singular reportaje sobre un torneo de pesca en la península de Yucatán.

“El Diario Del Ron” (1998), libro centrado en un periodista alcohólico, fue su única novela.

En “El Escritor Gonzo” (2000) se trataba su vida y su forma de hacer periodismo.

Al margen de estos títulos editados en español, Thompson también ha editado los libros de relatos “Kingdom Of Fear”, “Screwjack” y “Hey Rube”, y, entre otros volúmenes, “Fear And Loathing: On The Campaign Trail’ 72” (1973), crónica política que siguió la campaña presidencial de 1972 para la revista Rolling Stone, y “La Maldición De Lono” (1983), libro ambientado en Hawai.

En el año 2013, la editorial Gallo Nero publicó “El Último Dinosaurio” (2013), una recopilación de entrevistas al autor estadounidense.

Thompson fue miembro de la Asociación Nacional del Rifle.

En cuanto a su vida sentimental, Thompson se casó en el año 1963 con Sandra Dawn Conklin, con quien tuvo en 1964 a su hijo Juan Fitzgerald.

La pareja se divorció en 1980.

En el año 2005 se casó con su secretaria Anita.

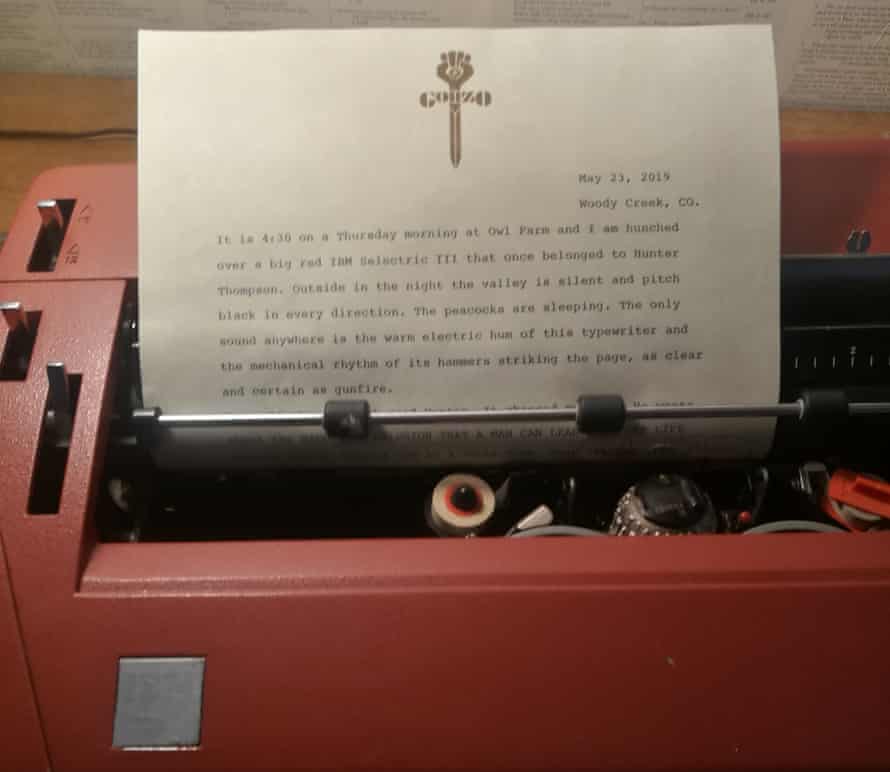

Se suicidó el 20 de febrero del año 2005, fecha en que se disparó en su cabeza en su rancho de Colorado.

Tenía 67 años de edad.

Fue incinerado.

Guía de sus adaptaciones cinematográficas y televisivas en AlohaCriticón

Comentarios de Libros

Miedo y Asco En Las Vegas (1971)

A decade after Hunter S. Thompson

|

Paul Harris/Getty Images |

|

| 1994, Aspen, Colorado, USA — ‘ Hunter S. Thompson Outside His Home.’ | Photo by Christopher Felver. |

I have worked as a journalist for the best part of a decade now, and there are elements of Thompson’s mythology I can no longer romanticise. There’s a section of Fear and Loathing that begins with this editor’s note: “The original manuscript is so splintered that we were forced to seek out the original tape recording and transcribe it verbatim.” Any illusion I once held that this was a sort of meta-joke was shattered when I read that it had been written up by Sarah Lazin, an editorial assistant at Rolling Stone in the 70s. “I had done a lot of transcribing in several languages,” she recalled last year in a Vanity Fair piece, “but this was pretty intense. In one of the tapes they’re in this restaurant, and they’re essentially torturing the waitress – yelling and screaming and throwing things – and I had no idea how to transcribe that.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario