“When I started to write about rural Tennessee, it felt as if something clicked. When I started writing about things I was absolutely familiar with, it came closer to working.”-

It positively worked. In a decade, Gay’s literary resume has gone from diminutive to demonstratively impressive. His award-winning short stories have been published in America’s most prestigious publications—The Atlantic Monthly, Oxford American, and Harper’s to name a few—and have been widely anthologized. He has authored three novels: The Long Home, which won the 1999 James A. Michener Memorial Prize; Provinces of Night; and Twilight, which was named the best book of 2007 by Stephen King. In 2007, Gay was named a USA Ford Foundation Fellow. On the horizon are Gay’s widely anticipated fourth novel, The Lost Country, and the film Provinces of Night with Kris Kristofferson playing a main character.

More than accolades, what matters to him most is writing a great scene and finding that key word that opens up the scene. As a narrator, he’s like a quiet old oak observing for hundreds of years at a time—a single human life too brief to study or tell the story. To add to that, Gay is masterful at opening lines. They’re perfect.

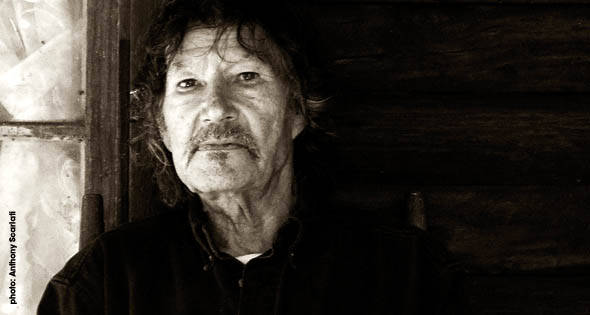

Being in William Gay’s world, it was as if I stepped right into any one of his novels. I could have expected Nathan Winer Jr. to come out from behind the cabin to go ginseng hunting. Normally it’s just he, accompanied only by the characters in his imagination. Today, Gay was ready for us with a flowing pot of coffee and an endless stream of cigarettes. I was contemplating my first question.

Night. Cold vapors swirled the earth like groundfog. Midnight maybe, perhaps later, it scarcely seemed to matter. The last ride had let him out on this road hours ago and he walked through a country which in these shuttered hours seemed uninhabited. Not even a dog barked. Just a steady cacophony of insects from the woods that fell silent at his approach and rose again with his passage, an owl from some timbered hollow so distant he might have dreamed it. Nothing on this road and he thought he’d taken a wrong turn but then it occurred to him that on a journey such as this there are no wrong turns. If all destinations are one it matters little which road you take. The pale road was awash with moonlight as far as he could see and in these clockless hours when the edges of things blur and the mind tugs gently at its moorings it seemed to him that the road had never been traversed before and once his footfalls honed away faint and fainter to ultimate nothingness it would never be used again.

– William Gay, The Lost Country

Where does your love of language come from?

I think sometimes you’re just born with something like that. My parents were great people, but they had no education. They were sharecroppers growing up on farms. They had maybe third-grade educations. By the time I entered school, I was scuffling trying to find books. I seemed pretty occupied with the written word. At some point it occurs to you, maybe you could write.

When I wrote The Long Home, I wanted it to be a myth some old man told you sitting in the yard. I wanted the same quality of myth that some of the old music had. I did consciously work toward that.

I like humor in stuff that I write. I always liked Mark Twain; there was quite a bit of humor in everything he did. Huckleberry Finn is one of the funniest books I’ve ever read.

I was always impressed by writers who were poetic. Most of the writers I admired I thought could have been poets. Thomas Wolfe—you could arrange some of his stuff in meter, and it would read like poetry.

What makes great literary fiction? What do you enjoy?

I haven’t really thought about that before. I read all kinds of stuff. Stuff that’s not great literature. I read a lot just for entertainment. But literary–I have different standards for literary writers. I think what I look for there is the same thing I try to do when I write. I want to depict the scene—whatever vision that the writer had—I want to depict it in a way I believe it, but at the same time I want the language to be impressive, make you think. The way a great poem stirs your imagination. Those are pretty high standards and not a whole lot of stuff meets them, at least in contemporary fiction. Like James Joyce and Faulkner and folks like that.

When I was a kid, I liked to read poetry. Thomas Wolfe’s language was really poetic in that way. When I first started trying to get published, I used to get a lot of criticism from editors who’d say I used too many metaphors and similes and quasi-poetic stuff. I should just tell a story. But I kept on doing the same thing. I was really impressed when I first read Cormac McCarthy. His language is like that, almost poetic sometimes.

What about Hemingway?

I like some of Hemingway. There’s some beautiful writing in A Farewell to Arms. When I was a kid, everybody was trying to write like Hemingway—everybody was writing that hard-boiled fiction. Everybody wanted to be Hemingway. He was a celebrity.

I sense a love of Steinbeck in your work.

Yeah, The Grapes of Wrath I remember being one of my most influential books. I think almost all my politics were formed by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

In what way?

I don’t know, populism. I’m like an anti-conservative. The Grapes of Wrath was a really compassionate book, identifying with the underdog.

Where does the creative process start for you?

What fascinates me is creation. Where stuff comes from like The Sound and the Fury by Faulkner—what made him do it? Why was he driven to do it? Even Faulkner couldn’t explain it. He tried, but even he did it just because he had to do it. He didn’t know why he did.

The moment of creation is interesting to me—even songs. I read a lot about Dylan. I think the guy is one of the few geniuses around anymore. I’d like to know what triggered those songs and where they came from.

Do you know how the story ends before you begin?

I have a pretty firm idea in general how it’s going to end. I don’t know specifically how it’s going to end. Sometimes it’s like a gift that you get. You’ve thought about something for a long time, and then one morning you wake up and it’s kind of clear in your head. The ending of Provinces of Night was written, but the woman who edited the book at Doubleday thought it should have an epilogue. She said, “I want you to write me a beautiful epilogue.” And that’s kind of a tall order. You can write an epilogue, but it might not be so pretty.

The Long Home is probably the most complicated plot that I’ve ever done. It was hard to work out the end of that book. There were several things going to happen at the same time, and the logistics…it was complicated moving everybody around, and it took a lot of work.

When do you know a book is complete?

I’m not sure that you ever know that for sure, like a definitive version of it. If I could go back and change things in some of my books, I would do some edits. Not anything major. I would do some tweaking. But to answer your question, you know on some subconscious level or something. By the time you get to the end, you’ve got a picture of it in your head, and when the manuscript that you’re working on matches the picture in your head as closely as you can get it…when you get as close to that as you feel you’re capable of doing, that’s it. Also, everything has to be resolved. Whatever situation you’ve gotten the characters into, you have to get them maybe not necessarily out of it, but they have to understand where they are or what they’re doing. And once you’ve done that, you’re pretty much through with it.

-If there were one book you could have written, what would that be?

The trouble with questions like that is I’ll tell you off the top of my head, but tomorrow I’ll say, oh man I can’t believe I said that! But I’m torn between All the King’s Men and As I lay Dying. I think As I Lay Dying, by William Faulkner, is pretty much the perfect book.

Is being part of the Southern gothic style something you think about when you write?

No. To shape something like that, at least for me, turns it into work. People who read books are pretty smart. They can tell when you’re being phony, and they can recognize honesty. I think I like Southern gothic just because I read so much of it when I was a kid. I read the early stories of Truman Capote, which were really Southern gothic. There was a book called A Tree of Night and Other Stories, and they were also gothic. They reminded you of Edgar Allan Poe; they were spooky and dark. One of the great moments of my life was in the drugstore when I was a kid. If I had any money, I’d look at the paperback rack, and I found a book called A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor. It was the best 35 cents I’ve ever spent.

In several of your stories you write about a place called the Harrikin. Is that a fictional or real place?

It started out as a real place. It was a big part of the southern part of this county—it used to be owned by [a big] corporation. There used to be iron furnaces where they made iron and shipped it out. It was a little town almost, but I guess when the ore was depleted, they moved everything out. The people there had to leave too. It just deteriorated. It couldn’t be developed, because it belonged to this company, so it just grew wild. I used to go down there for ginseng. Actually I just liked to wander around. It was a really interesting place. It was interesting trying to figure what their lives were like, the struggles of the people who lived there.

How did Provinces of Night materialize?

When I wrote Provinces of Night, I thought it was a short story. I wrote a scene about the boy, and I got so interested in him and how he wanted to write for a magazine. All the time I was working on this book, I was listening to Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, folk music from the 1920s and ‘30s. There was a banjo player from West Virginia, Dock Boggs, on there who was really interesting. His songs were really dark. He was a dark guy. And he [the grandfather] took on some of Dock Boggs’ characteristics. I made him an ex-musician then, instead of a demolitions man.

Who are some of your favorite characters that you have created?

Probably my favorite is Bloodworth and his grandfather in Provinces of Night. I’ve written a bunch of spooky characters, and if I said they were some of my favorites, people might think I need some psychiatric care. The guy Dallas Hardin [The Long Home]. Or the kinky undertaker or hired killer in Twilight. I like Edgewater [The Lost Country] because he’s different from his environment. He sort of wanted to be a writer.

Can you tell us how Twilight came about?

Twilight came from a thing I saw on the news. There had been an undertaker—I think he was in Franklin, actually—who had been caught doing some atrocities with dead bodies, dumping garbage cans into coffins and that kind of stuff. And I wondered if a guy was respectable, you know like upper-middle-class income, what he would do to protect that reputation. So I wrote a story about a brother and sister who had discovered that their father was mis-buried, and they tried to blackmail this guy. But then I saw it wouldn’t work as a short story, and I wrote Twilight. That was the easiest of the books that I did. I think I was laying brick or maybe working as a carpenter during the day and wrote it at night. I wrote it really quickly, maybe three months or something.

Stephen King named your book Twilight the best book of 2007. How did that make you feel?

Really surprised, mainly. I had no idea he even read the book. I subscribed to Entertainment Weekly, and I always read his column. I read from 10 up to 1. I was shocked when I saw my name.

The South you write about no longer exists—what do you think happened?

I don’t know. I think it was drugs and television. I think when people began to get TVs, and people could see situations on TV like the Cleavers, the regionalism began to kind of slip away. Things were becoming more generic. Especially with the Internet. Everybody has access to everything. It all seems to be becoming one global place.

You said that good writing needs to have depth, and it ought to be about things that really matter. What really matters to you?

What really matters to me when I write something is to evoke a scene, to find whatever word works that’s like a key that opens up the scene. If I wrote a good line or good scene or complete story, there was no feeling like that; it was better than alcohol, drugs or sex or anything. You go around high for hours, because you accomplished what you sort of set out to do. And I think the most important thing is to write a scene so whoever’s reading it recognizes it. They may not recognize the actual situation, but the emotion, whatever emotion the scene evokes.

-Nashville Arts Magazine would like to give our sincere thanks to Landmark Booksellers for their assistance arranging this interview. Landmarkbooksellers.com

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario